Austen's Arcadia

IN A STRANGE AND VIRTUALLY UNREADABLE essay on the settings of Jane Austen’s novels, the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner laments Austen’s vagueness in describing buildings.

Not only vague, he suggests, but positively negligent. Austen seems studiously to avoid any opportunity for description. Houses are ‘fine’, ‘grand’ and ancient or modern, but that is about it.

When Wickham, in Pride and Prejudice, is said to have given a detailed description of Pemberley, the grand Derbyshire house of Mr Darcy, ‘we are not allowed to hear it’, complains Pevsner. Wicked Wickham.

Such a description in Wickham’s mouth would probably be as dry and punctilious as those of Pevsner himself. In his essay Pevsner lists all the houses Austen knew, all those she might have described, is exasperated that she did not, and ends by admitting only that she at least knew all the most appropriate addresses for her characters in London and Bath. He then goes on to list them all, like an Austen address book.

Pevsner’s strange, desiccated article does at least point to what might be described as the remarkably un-visual nature of Austen’s novels. Her fiction contains no illuminating descriptions of works of art, of interiors, of buildings — descriptions so that we might see those things.

In Pride and Prejudice we see the world through the eyes of Elizabeth Bennet, who is so busy analysing human motivations that she has no time to notice the pattern in the carpet, or what is on the mantlepiece. Seeing for Austen is understanding, where seeing, by contrast, for Dickens, is actually seeing. ‘Elizabeth knew nothing of the art’, Austen writes, perhaps also describing herself.

For these reasons, it might seem pointless to ask, as has often been asked, whether Darcy’s Pemberley is based on Chatsworth House. And yet it isn’t entirely pointless, for the reason that I feel quite sure that it was, and that the moment of arrival of Chatsworth is (quite possibly) quite unique in Austen’s fiction.

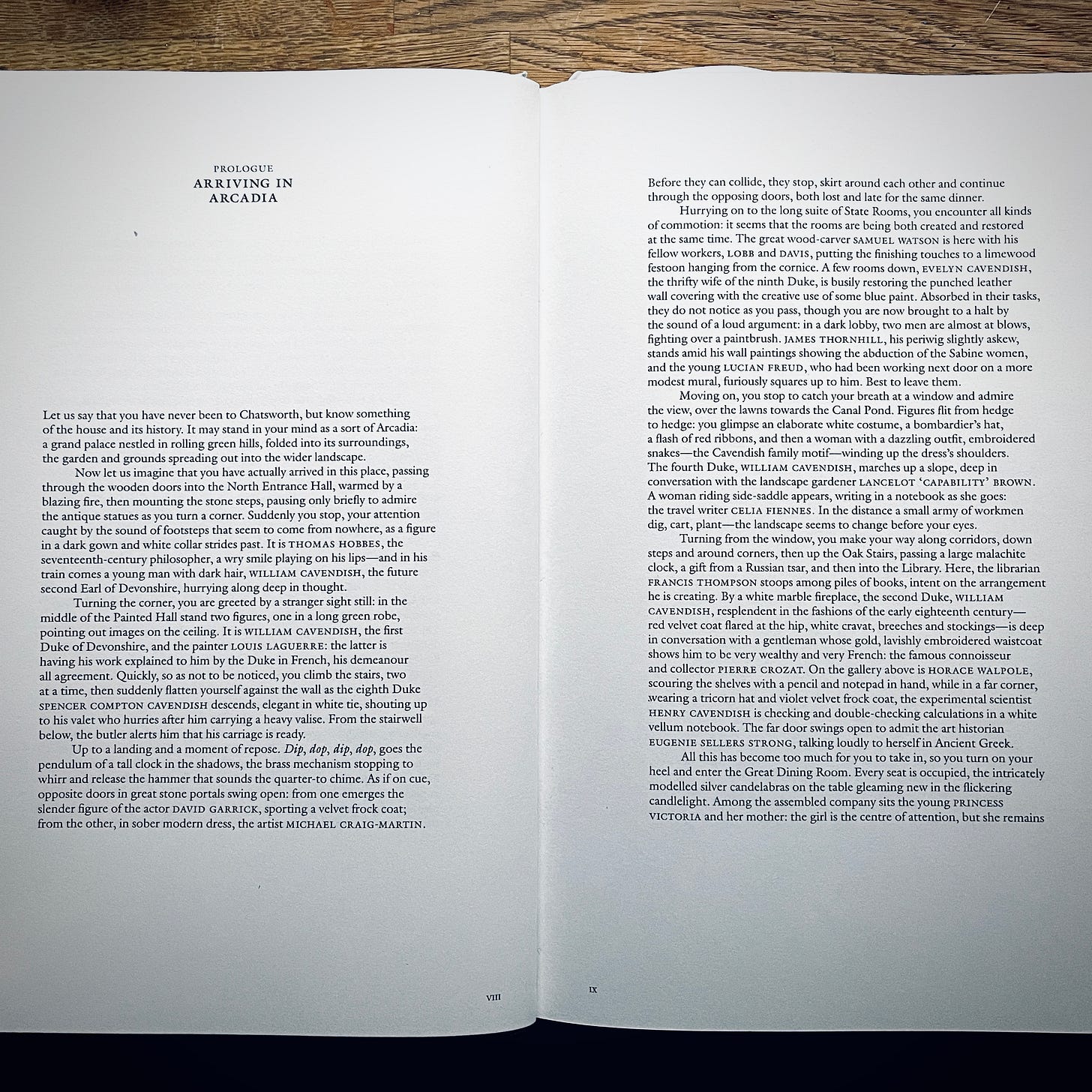

Elizabeth Bennet, as you will remember, goes on a tour of the north with her uncle and aunt, the Gardiners. She arrives at Pemberley as an ordinary house visitor (thinking Darcy is not there), wanting to look around (Pevsner reminds us how common this was at the time, country house owners complaining of being overrun by noisy sightseers).

Austen’s description of the approach, with the hills looming behind, and the natural banks of the river, and the curving of the road, is not entirely topographically clear, but is entirely the feeling of arriving at Chatsworth House:

It was a large, handsome, stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills;— and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by awkward taste.

They are led around by a housekeeper and admire the views through the windows:

Every disposition of the ground was good; and she looked on the whole scene, the river, the trees scattered on its banks, and the winding of the valley, as far as she could trace it, with delight. As they passed into other rooms, these objects were taking different positions; but from every window there were beauties to be seen.

This seems all very accurate. The different and often ravishing views of the grounds and surrounding landscape are just what you see nowadays.

What really clinches the question is that, despite her indifference to art, Elizabeth is unable to avoid the paintings hung around the rooms. Something about the setting makes them super-visible, super-alive.

On passing through the door into the house she is suddenly awakened, or at least roused from terminal slumber, to the impression works of art can make. Her attention is mostly taken by portraits, which appear like real presences of characters elsewhere in the novel.

It is naturally the portrait of Darcy that she finds most captivating, and makes her deaf to the housekeeper’s descriptions of the other pictures, the rooms and the furniture, (which we are also denied, presumably again to Pevsner’s chagrin). She knew nothing of the art, then, but everything of the people.

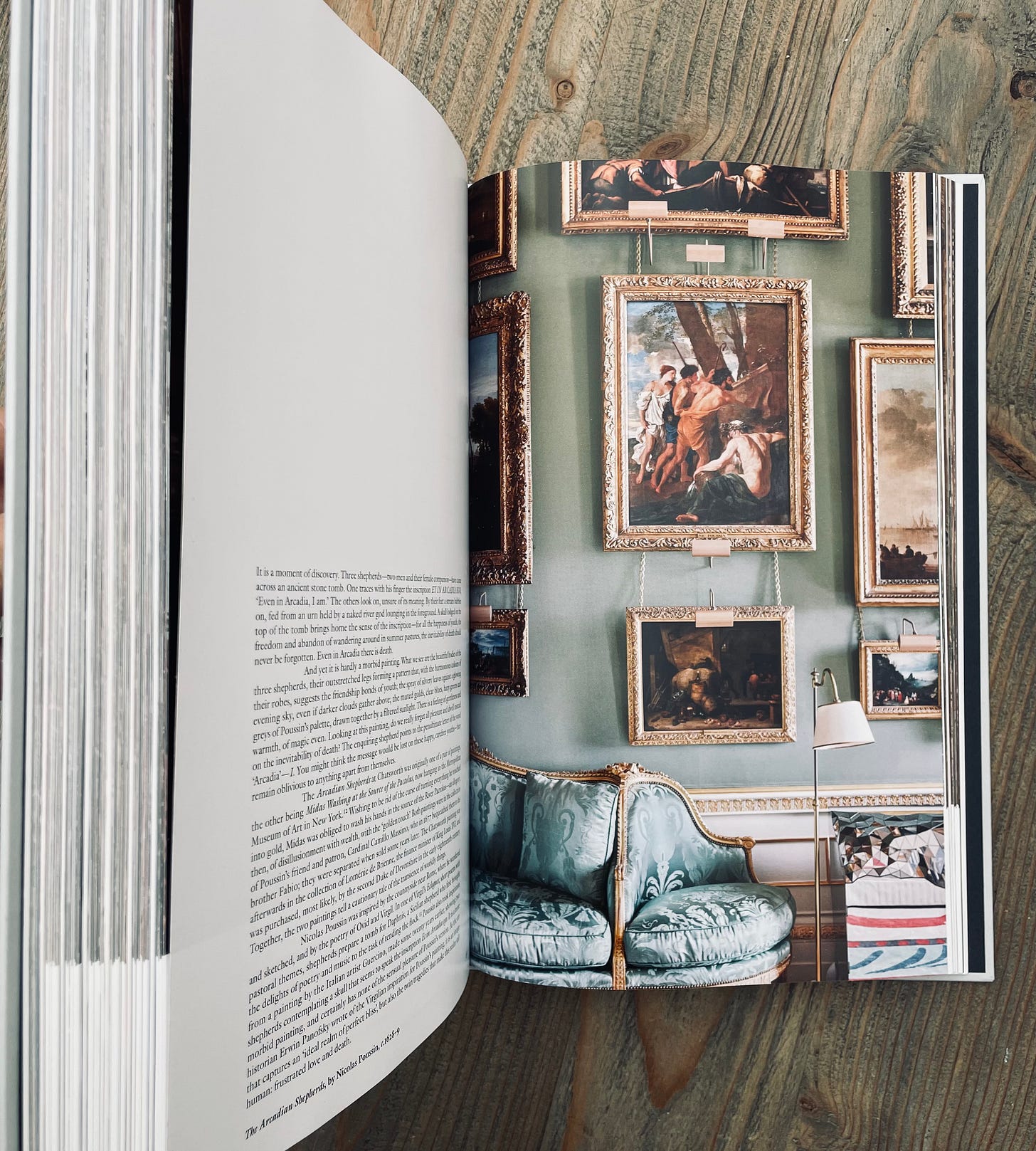

When they finally visit the picture-gallery, she ignores Poussin’s famous Et in Arcadia Ego (Austen doesn’t even mention it), the beating heart of Chatsworth, and spends her time looking at pencil drawings by Darcy’s sister. It is the artist, not the art, that counts.

It would of course have been remarkable to read Jane Austen’s response to Poussin’s famous painting. But it should also be said that there is no sure evidence that she actually visited the house. All of this is really just supposition.

As Pevsner wrote about Chatsworth in the 1930s, there is ‘material for a whole book’ in its collection of Italian paintings alone, alongside ‘the most beautiful private collection of drawings in existence’. There really is nowhere else like it, and I like the idea that not even Austen could be impervious to the remarkable combination of art and setting at Chatsworth, a true Arcadia.

But, in a perfect world, in an Arcadia, would we need works of art? Would we not all be creative spirits, would not everything take on the aura of art? Would all art become the best form of art, which is poetry?

Idle thoughts, perhaps, but which came back into my mind recently on learning of the death of Tom Stoppard.

Stoppard had been a regular visitor to Chatsworth, a friend of Deborah and Andrew Cavendish (the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire). He knew the area well. In younger life he had lived in a house close to the nearby village of Baslow (‘so do I’, joked the Duke).

In her superb biography of the playwright, Hermione Lee relates who fascinated Stoppard was by Chatsworth and the experience of being a house guest — always feeling ‘something of an impersonator, or imposter’.

Just the kind of awkwardness that a writer needs, perhaps, to jar the mind into interesting ways of thinking.

In the Pinetum at Chatsworth, a sort of ‘grove of worthies’ up on the ridge behind the house, there is a portrait bust of Stoppard by Angela Conner. It is one of a number of portraits, resting on simple wooden posts, showing family members alongside famous house guests, including the unlikely company of Lucian Freud and John Betjeman (did they ever actually meet?).

Tom Stoppard’s great play Arcadia, taking as its subject the parallel creative energies of art and science, explored in the setting of a country house, must have been at least in part inspired by his visits to Chatsworth — he even mentions the house and the Duchess of Devonshire towards the end.

Stoppard’s reflections on landscape gardening seem to combine the view from the window at Chatsworth, with the memory of Poussin’s painting:

English landscape was invented by gardeners imitating foreign painters who were evoking classical authors. The whole thing was brought home in the luggage from the grand tour. Here, look - Capability Brown doing Claude, who was doing Virgil. Arcadia!

I had not read the play until I stumbled across a copy in the Oxfam bookshop on Kentish Town Road in early 2018.

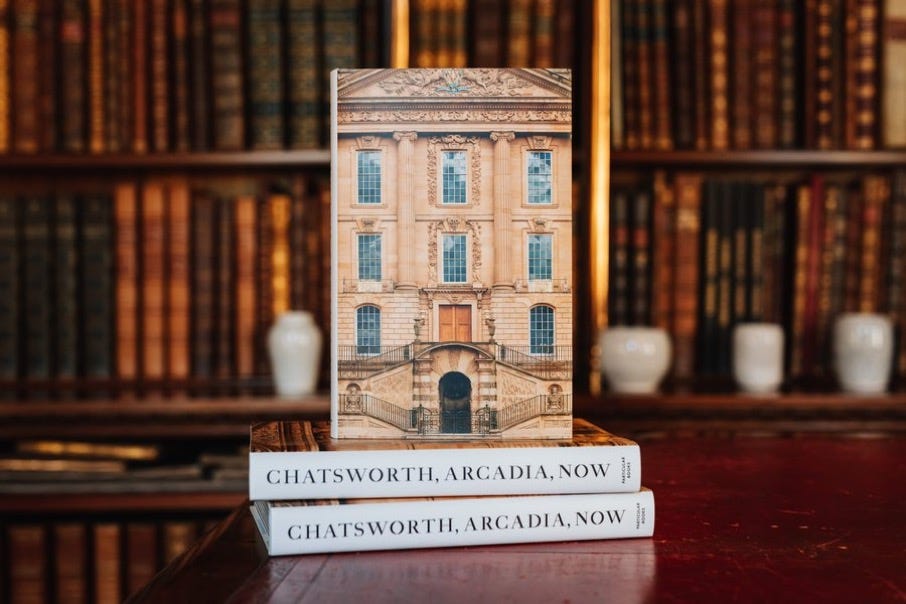

It was an absolute gift. At the time I was attempting to write my own book about Chatsworth and its great art collection, published a few years after by Penguin as Chatsworth, Arcadia, Now (and which, I should add, is the perfect Christmas present for the art lover in your life).

The book was a commission from the Duke of Devonshire, and involved a significant amount of research into the history of the house and its great art collection, and just as much, if not more time wandering the rooms and corridors and the grounds outside, wondering how to put it all together.

What links the great sculpture gallery with its works by Canova, with the old master drawing collection and the great collection of Dutch and Italian painting with the many wall paintings around the house, not only the famous paintings by Lucian Freud in one bathroom (which you could still use), but also including the great ‘Sabine Room’ (which for a couple of weeks during the winter months served as my writing room)? Not to mention the great collection of antique gems, the vast largely uncatalogued library of antiquarian volumes, and also the astonishing collection of contemporary art, including many remarkable commissions… The list never stops.

I was looking for a single word, which came to me at 9.23 on the 28th March 2018 (I recorded this with a tweet — in the old days of twitter): Arcadia!

The house itself had provided the answer, in the form of Poussin’s great painting, Et in Arcadia Ego — ‘even in Arcadia, I am’ — written on a tomb, and therefore meaning ‘death’. Behind every dream of happiness is the reality of mortality. And so on. And also, it might be said, the reality of death duties, but that is another story.

It was a few weeks after this revelation that I came across the copy of Arcadia in the second-hand bookshop on Kentish Town Road. At the time I wrote in my diary:

Stoppard’s Arcadia: brilliant, changes everything writing the Chatsworth book. Must be more simple, cleverer, funnier. Must take more account of science (Henry Cavendish etc) and the layering of time. Difference between inexorable technical progress and the eternal return of art. Backwards chronology fascinating, unnatural, artificial: against science, for art. ‘To go through the door there has to be a house’, or however Stoppard puts it. Chatsworth a place of spirits and ghosts, where time can flow backwards and also be overlaid, without distortion.

Quite how much of this was achieved I’m not entirely sure, especially with so many people looking over the text and making demands of a book that was also supposed to be a perfect sort of object, a chunk of Chatsworth itself (every sentence had to reach the end of the line, for example, so as not to leave empty spaces in paragraphs).

Many of my own inadequacies were compensated for by Victoria Hely-Hutchinson’s remarkable photography of the house. But when I had finished writing, and the texts were being assembled with images, there still seemed something missing.

I realised, perhaps half with Austen in mind, that what made Chatsworth so remarkable was not really the great collection of art at all, but rather the people and characters who had passed through the house and left their traces there, often in the forms of works of art, and not all of them by any means portraits. This was not by any means an original thought, but it meant a lot for having come to it the hard way.

At the least minute I wrote a prologue, ‘Arriving in Arcadia’, summing up this feeling. It seems now more like a homage to Jane Austen and her imaginary visit to Pemberley.

Somewhere — perhaps in Hermione Lee’s brilliant biography — that Stoppard was a collector of first editions of Jane Austen. Perhaps he had said this himself, when we spoke, all too briefly, about Chatsworth. He had given the Duke of Devonshire a specially-bound copy of Arcadia. He liked my prologue.

In any case, I regret not having the chance since (and now of course not at all) to tell him of a chance discovery in the library at Chatsworth, where I spent a magical week in the freezing ‘beast from the east’ winter of 2018.

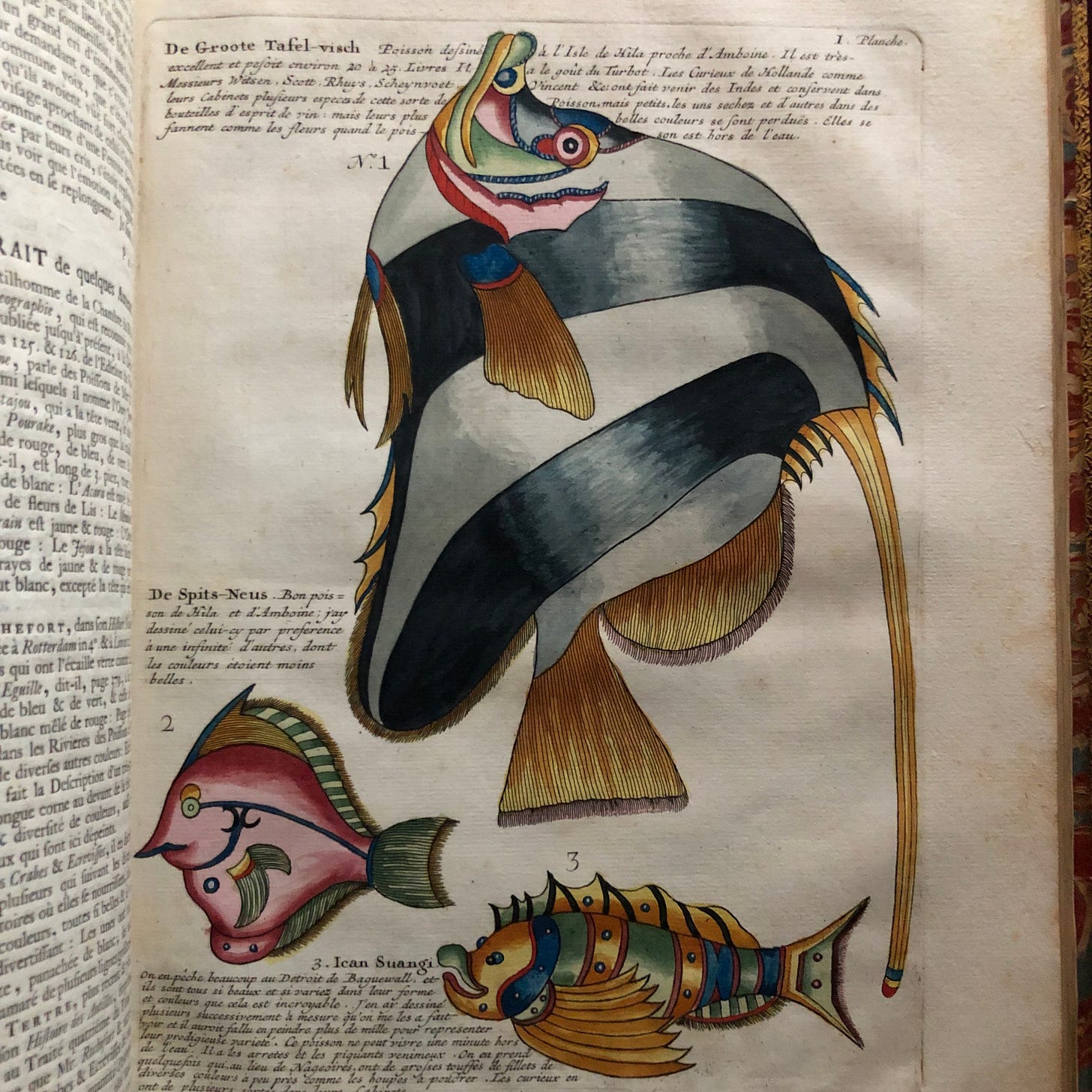

I was going through the remarkable and largely uncatalogued holdings of folio volumes of prints and drawings, as well as the many scientific tracts going back to the Renaissance, and copious strange and wonderful works of natural history.

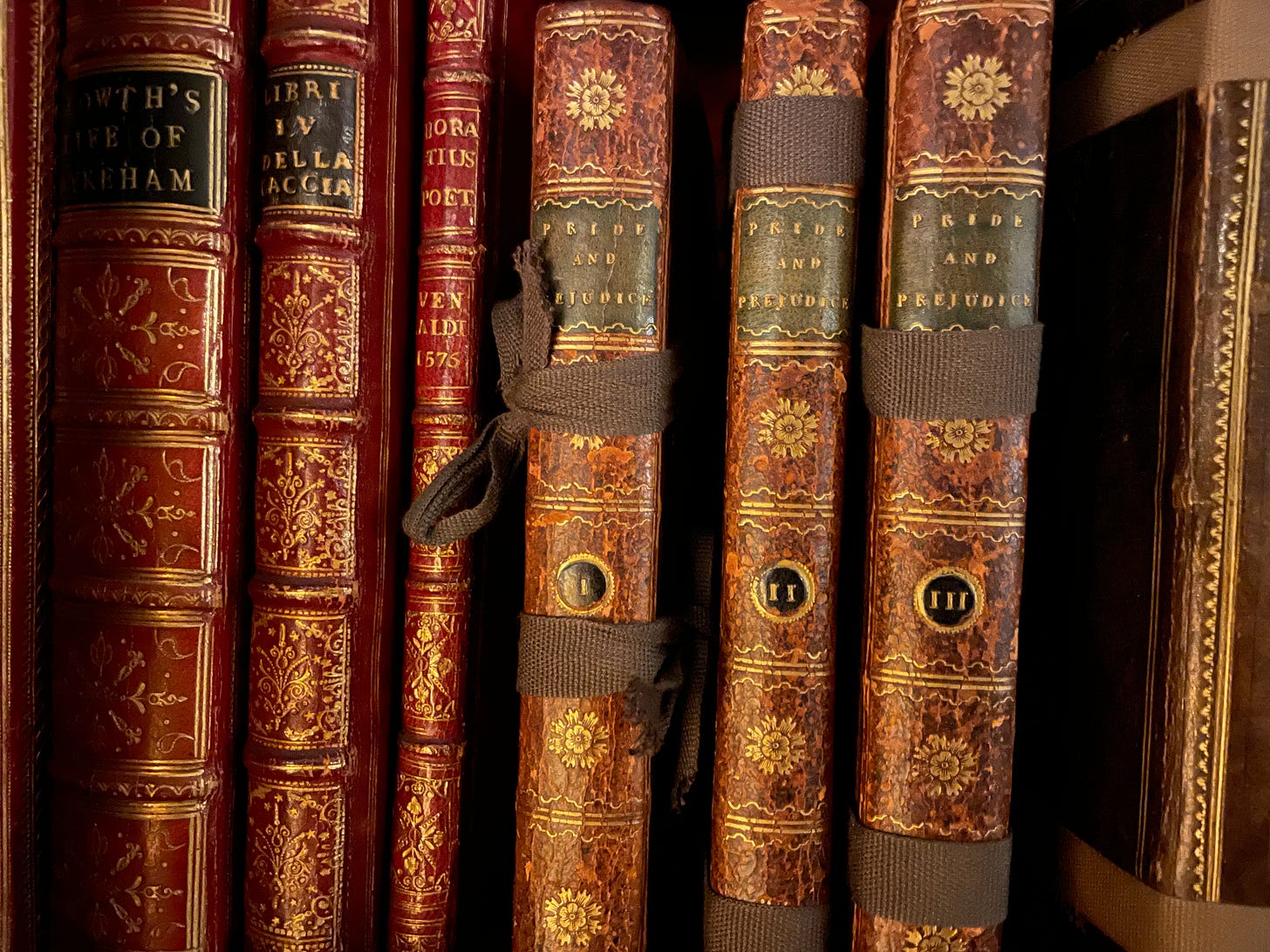

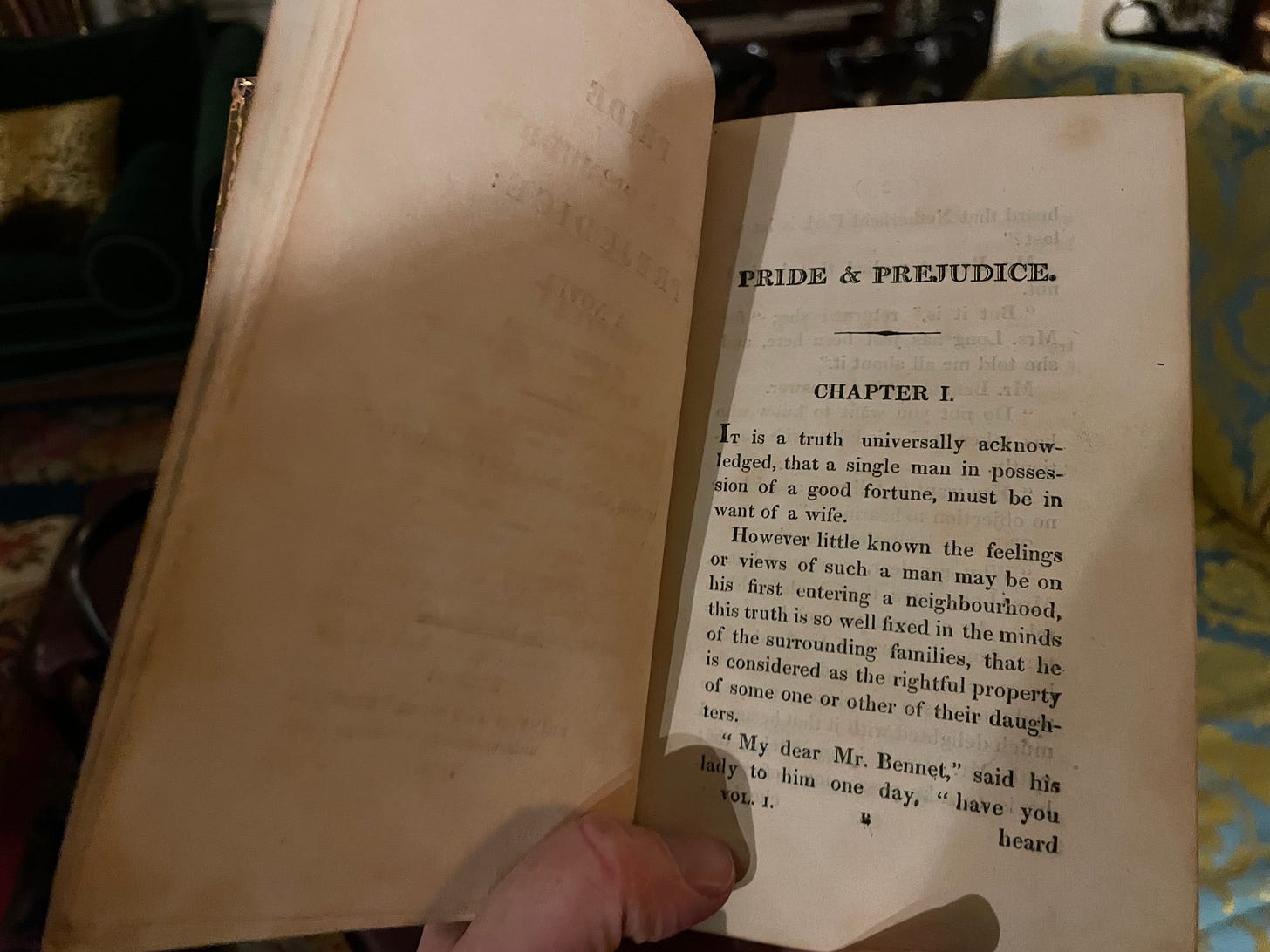

Next to the fireplace was a smaller shelf of leather-bound books with gold-tooled spines. One of them was a first edition (in three volumes) of Pride and Prejudice, gently bound with strips of cotton to keep the boards in place.

It had clearly been read many times over.

The fire was roaring and outside there was snow and a freezing blizzard.

So I sat and read it again.

Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘The Architectural Setting of Jane Austen’s Novels’, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute, vol.31 (1968), pp. 404-422.

Susie Harries, Nikolaus Pevsner: The Life, London 2011

Hermione Lee, Tom Stoppard. A Life, London 2020

Thank you so much for this beautiful essay/reflection, which combines so many things I love. Chatsworth is my Arcadia too; I fell in love with a photograph of it when I was 11, and declared then that I would work in that building when I grew up, which I did for 19 years, leaving in 2010. Debo was my boss, patron, inspiration and eventually friend. Through her, I had my only encounter with Tom Stoppard. He was due to compere an event when she and Patrick Leigh Fermor would discuss their collected correspondence, recently published, and she asked me if I would introduce Tom. She pretty much told me what she wanted me to say, with a tease or two built in, so that part was not too hard. But a few weeks before, I was suddenly invited up to the Old Vic in Edensor for lunch, 'to meet Tom'. I had only recently returned from giving some lectures about Chatsworth in America, to accompany an exhibition. I arrived with trepidation, to find we would be four for lunch, the other guest being Debo's niece and editor, Charlotte Mosley. Tom arrived in the dining room last, smoking, of course, and we sat. Debo, sensing my nervousness, opened the chat. Looking across the table at Charlotte, she said 'Oh Char, aren't we lucky, sitting here with one of the greatest communicators in the world....and a man who writes plays.' We all chuckled, and before I could demur, Tom put his cigarette down and said 'That sounds about right' and off we went. It was typical of Debo's ability to level the playing field when she chose, and he was a sport to go along with it. And as so many of the tributes to him from his eminent friends have said was typical, he deployed his open curiosity, asking me lots of questions about what my first job there - car parking & lavatory cleaning for a summer - had been like and what I had learned about visitor preoccupations as they arrive after a long drive. I walked away from that lunch with my head in the clouds and my feet on air, and thankful that I hadn't gone all fan-boy and told him how much I admired his plays, Arcadia especially, given I'd have had nothing intelligent to say about them. One more thing, about Chatsworth and Pemberley. When the Joe Wright film of P&P was made, I was asked to do a filmed interview, for the DVD 'extras', about Chatsworth as a location for the film. They were especially keen that I link the description of the arrival at Pemberley with Chatsworth, and while I was careful not to say that we 'knew' she based it on Chatsworth, and said that it was a possibility and anyway, once the film was out, that's what people would believe. A distinguished local historian got in touch once the DVD was released, furious with me for not debunking it, on purely economic grounds. Darcy, he said (rightly) is untitled and described as being very rich on 'ten thousand a year', while the contemporaneous 6th Duke of Devonshire is an aristocrat who had an income of anything between £70-90,000 a year. Mr Darcy simply could not have afforded to run or live in a place the size of Chatsworth, his income would not have been sufficient and the wretched film had inflated our sense of Darcy's wealth to oligarch levels, which was silly, and upset the delicate social web of the book, which, with the exception of Lady Catherine de Burgh, is between levels of the gentry, not the aristocracy. That was me told. He may have been right, in purely economic terms, but he was I felt overlooking two things. Firstly, in the medium of film, what has to be communicated instantly and visually is 'huge unobtainable wealth' not historical accuracy, and Chatsworth did that very well. And secondly, there is no reason why Austen might not have been inspired by Chatsworth's setting and approach through the landscape, as you suggest here, without meaning to imply in her text that the house was as enormous (she calls Pemberley 'large') as the reality she may have seen. I tried to make these points to the historian; he was not impressed. Anyway, thank you for combining three great loves of mine - Austen, Stoppard and Chatsworth - into one, for me, very plangent essay.

I wondered where you were taking me but the destination, as it came into view, seems absolutely right.