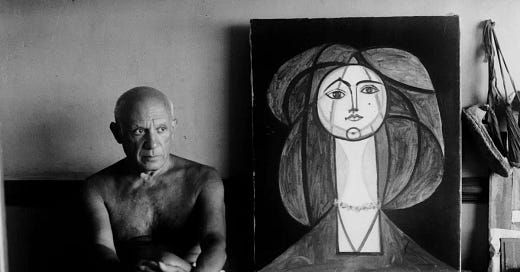

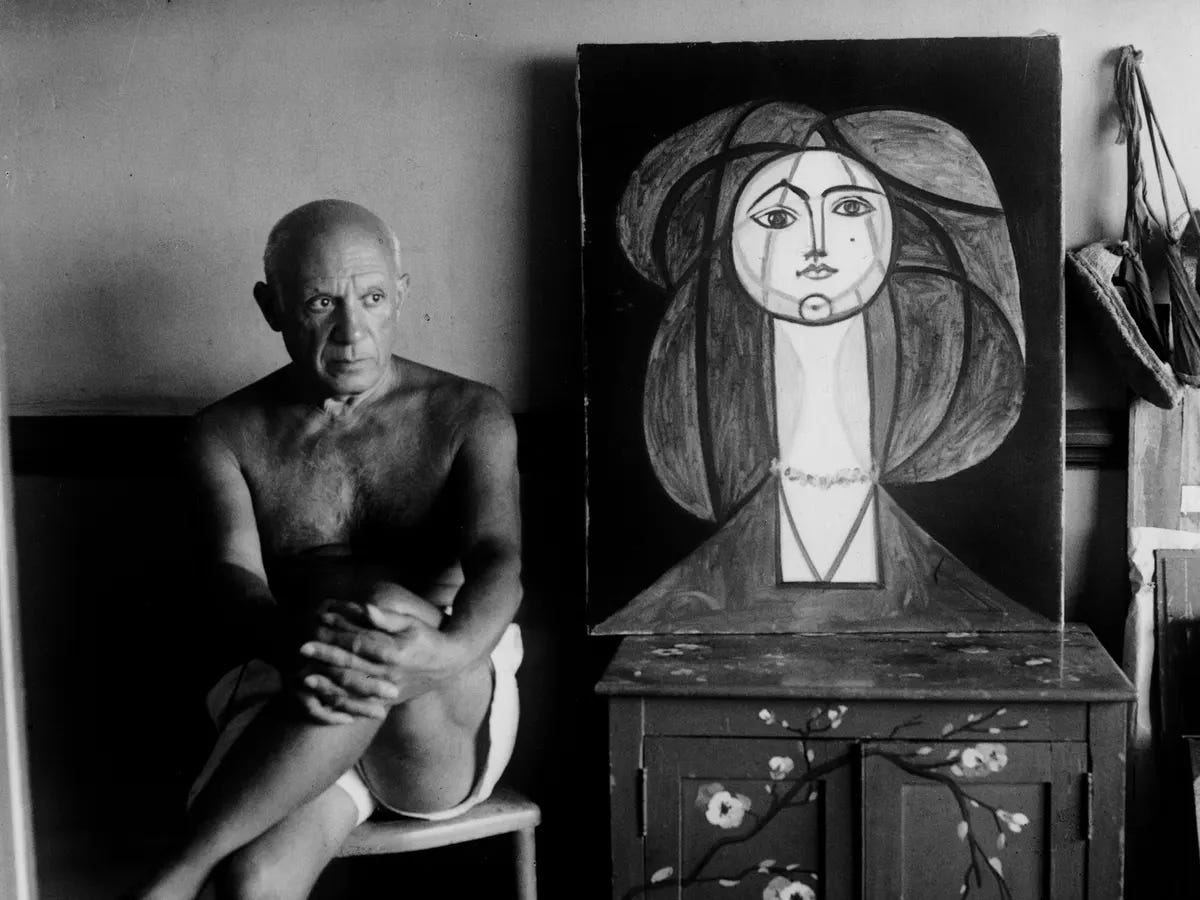

WHEN PABLO PICASSO DIED, FIFTY YEARS AGO, he was a well-known and celebrated artist, but was hardly at the summit of his fame. Shortly after his death an exhibition of his recent paintings opened at the Palais des Papes in Avignon, hung close together on the stone walls of the palace chapel. The show was at best ignored, but otherwise derided, even by long-term supporters of the artist — the loosely painted canvases, showing childish-seeming figures, were deemed the weak gestures of a mad old man whose genius had long faded.

It didn’t take long, however, for them to be brought back into the canon, becoming another twist on the long tale of Picasso and his art, forever evading description, forever defying expectations — always one style ahead of his audience, so it was said. Whatever attacks might be levelled at him, ad hominem, or ad opus, so to speak, there is little that can be done to dislodge his legend, nor derail his auction prices. He is guaranteed to draw a popular audience, but also provides rich grist for the most recondite of academic mills. The academic art historian T.J. Clark’s brilliant lecture series, published then years ago as Picasso and Truth, are a recent case in point.

On the fiftieth anniversary (some might say celebration) of his death, however, his legacy could not be more contested. That an artist who once described women as being either goddesses or doormats can be shown at all nowadays might come as some surprise. It is almost impossible to imagine Picasso being alive and working now — he would be his reputation’s own worst enemy. Part of the fact that his works have survived, and they undoubtedly have, is down to the sheer weight and volume of what he created — to suggest the most trivial justification of value, he is probably one of the most successful artists at auction of all time. Even if you wanted to de-platform, cancel, call out Picasso, he would simply reappear somewhere else, inviolable, inscrutably there — or more to the point, still here. The very name ‘Picasso’ seems to have become a unit of aesthetic stability and weight, an irreducible essence of art.

The fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death has been a strange, mixed affair, the sort of party where truths are told, hardly a celebration at all, but more like group therapy. This is how it feels, at least, watching the BBC documentary Picasso: The Beauty and the Beast. The words ‘We need to talk about Picasso’ are flashed at the outset of each of the three programmes, which consist of numerous talking heads giving their view on Picasso’s conduct in his private life, and occasionally talking about his art.

As an enquiry into Picasso the man, The Beauty and the Beast is successful in puncturing much of the legend, and showing how essentially shabby he could be — embarrassingly adolescent even. He gets up at midday every day, in a bad mood. He never learns to swim, so pretends at the seaside, keeping one foot on the seabed. He is quick to take offence, and is hardly the most loyal of friends. The programme does a good job of making all these points, bringing him down to earth, but also, largely through the commentary of those such as Philippa Perry, Louisa Buck, and Alexandra Schwartz, of making the dizzyingly basic point that his actions ought to be seen in context.

The documentary says as much as needs to be said on the matter of Picasso, biography, gossip, personal history. Some of the speakers seem put out, embarrassed even, to have to recount such a simple, well-known story, when clearly there is so much more to say about the actual art – the real conversation that ‘needs’ to be had. And it is when the focus falls on the art, and the critics and curators are allowed to express their own thoughts and opinions, that the programme takes off. Louisa Buck is excellent on the portraits of Olga, and on the possibility that Picasso is ‘emoting’ with her pensive, inscrutable presence, trying to communicate how she feels. Jenny Saville describes what it is like to be a painter at night, in the city, where your only companions are drunks, wayward, lost people — an old man sitting on the corner with a guitar, a couple sitting silently in a late-night bar. Picasso ‘owned’ his dark side in his minotaur prints and drawings, Phillipa Perry argues, which is very advanced psychologically, she adds — although there is no evidence that he ever underwent psychoanalysis (I don’t think), rather sending Françoise Gilot, bizarrely, to Lacan, in lieu of pre-natal care.

The voices and recorded presences of Picasso’s partners play an equally important part in this group therapy. Marie-Thérèse Walter, being interviewed on radio in 1974, is posed the question of being so young when the forty-five-year-old Picasso met and seduced her. ‘Well, I was seventeen’, she replies, with a sort of bravura naivety. ‘You told me he was wonderfully terrible’, the interview asks. ‘Yes, fortunately’, Walter replies, ‘otherwise I wouldn’t have liked him’.

Film footage shows the elderly Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s lover in his earliest days in Paris, revisiting the Bateau Lavoir, their old digs, in the 1950s, trussed in raincoat and headscarf. ‘Why do you knock on the door’, the unseen interviewer asks, as she turns around from the building. ‘Because of memory. But now it is empty. I am sorry for it’, she tersely replies, like a character in a novel by Marguerite Duras.

There is no testament from former lovers and partners, at least in this programme, which forms much of a case against Picasso — rather the opposite. Frances Morris, a former director of Tate Modern, recounts a visit to Paris in 1990 to track down Dora Maar, his lover during the late 1930s, to ask her about the 1937 painting Weeping Woman, for which Picasso used her as a model. ‘Oui, c’est moi!’, Maar says, opening the door to Morris. Her tears, she said, were for the state of the world, rather than a result of Picasso’s maladroitness. Only a late interview with his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, given after Picasso’s death, gives a sense of the loneliness that many of his partners felt when the relationships were over – after being for a time at the centre of the world, it was hard to live in the half-light of the ordinary world.

Surviving children and grandchildren give what must be rare, and valuable interviews — considering the recent deaths of Françoise Gilot and her son Claude Picasso, as well as Maya Widmaier-Picasso, the artist’s daughter by Marie-Thérèse Walter. Françoise’s daughter, Paloma Picasso, is one of the most articulate and level-headed of the grandchildren, whose characters might all be traced to the grandmother who once went through the mill of Picasso’s love — an experience that only Gilot really survived, for the reason that it was she that left him. One of the two very moving moments is the footage of Françoise on horseback, opening a Corrida — Picasso had requested that she do so, after they separated, as a homage to her and valediction for their relationship. She left him in grand style, says her daughter Paloma, with moving pride. The saddest story, however, is that of Paloma and Claud being cut off from their father, after their mother published her intimate memoir of Picasso. 'I made a point every year of going down to my father's house and ringing his bell at least three or four times, until he finally passed away', Paloma says. The meaning is mangled and unintentionally funny, but clear and moving all the same.

But there is only so much of this that can engage our interest – the real substance of the documentary is the art itself, and it is here that the outside voices, of critics, writers (including, notably, Colm Tóibín) and artists is so valuable. If you ignore the art, the story is easier to tell. But you also ignore the reason we are so interested in Picasso in the first place — the gossip, in its basic substance, could be about anybody. Only Picasso could have painted Guernica, or the portraits of Marie-Thérèse in the 1930s, or made the late paintings, which far from being expressions of weak old age, signposted the art to come, from the paintings of Julian Schnabel in the 1980s to those of Tracey Emin today (she would have been an excellent participant in the Picasso Group Therapy session). Cubism, although it has precious little influence on art today, and was a group effort, was perhaps the most revolutionary style of art ever to have been created — and only Picasso could have made a painting as out of time as Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon from 1907. Like the famous quote about the French Revolution, when it comes to describing the influence of such a work, it is still too early to tell.

The question of Picasso’s personal life will not, and should not go away. It is true, as someone remarks towards the end of the programme that we we can often feel uncomfortable, complicit even, looking at those works which figure an act of sexual power-play — the hulking minotaur, having his way with the limp young girl. But it is precisely this discomfort, this strangeness, this risk — uprisking, perhaps — that Picasso took as the foundation for his art — an art that by necessity goes beyond the facts of his private, and public life. It is not a diary. That is why it still speaks to us today.

As a bonus, here is a short film that I made summing up the stages of Picasso’s work in just under a minute. Showing it in lectures I attempt to give a running commentary but can never quite catch up. Enjoy!