I wrote an article for The Art Newspaper about works of art as living things (link below). Here is some art historical background to this train of thought, based on a recent lecture.

BEFORE ART, CAME IMAGES. It is an astonishing idea and, once you get your head around it, one of the most powerful ideas in the history of art.

The Era of Images lasted, very roughly speaking, from the rise of world religions in the first century AD until Giotto and the first moments of the Great Awakening (see previous post) in the early 1300s.

A good introduction to the idea of ‘Images before Art’ is the German art historian Hans Belting’s 1995 book Likeness and Presence.

For Belting the era of ‘Art’ appears after the Middle Ages (after Giotto, then), and is a time when art is being made by recognised artists and being discussed according to theories which take into account the different philosophical ideas around works of art.

Art becomes a way of knowing the surrounding world, a path to knowledge, and mingles with science as much as it welcomes in elements and images from the familiar world — think of Giotto painting Halley’s Comet above a nativity scene acted out by people from his home town, including a stable boy who seems drawn from life.

It is the ‘Art’ that we know nowadays — a subject to be approached in the spirit not of a theologian explaining religious faith, but with the critical spirit of philosophy, or perhaps even sociology. (There is an excellent essay by Arnold Gell, ‘The Technology of Enchantment’, on this question).

What we take as a history of art, Belting writes, is in fact a history of artists (you might remember another famous quote to this end…).

The Era of Images - what came before Giotto - is harder to describe. It doesn’t fit into the same developmental story of styles. Images like the famous Mandylion (above) have a sacred power derived not from the signature of the artist who made them, but from the communities in which they were made and the uses to which they were put – from aids to personal prayer to deployment as battle standards, images that could defend an entire city.

The really important point is that these images — and here I mean the Byzantine icon paintings and mosaics that are the subject of Belting’s book — were seen as living things. You could talk with them and expect a response. If they were attacked, they suffered. If they were properly venerated, they returned the favour.

Like organic living things, their creation was more or less miraculous. The Mandylion appeared on a cloth after as Christ mopped his brow with it - a class of images known as ‘acheirpoieta’, a beautiful old Greek world that means images made without human hand.

In a recent lecture Seven Types of Ambiguity (title of course borrowed from William Empson’s famous 1930 book), I attempted to describe some of the different ways in which images confront the divine, the beyond, the world of the unseen — and how this still shapes our view of art today.

What might be these seven type of ambiguity — the varieties of mystery in art in the pre-scientific world?

One, abstract afterlife

The greatest ambiguity is death itself — or perhaps rather what happens after death. Since the first stirrings of human civilisation, objects have been created that reflect this ambiguity, grave goods, as we now call them, that show our first attempts to reckon with the abstract thought of dying — the physical impossibility of death in the mind of someone living, as it has been described.

They are many and various, but these objects all have one thing in common, which is a highly ambiguous abstract quality — as if their makers were trying to create symbols adequate to the mystery of death.

Among the earliest known are Bi Discs — perfectly-carved jade (nephrite) discs with a perforated centre, which were laid on the bodies of the dead in ancient China.

Nobody nowadays is quite sure what they symbolised, but perhaps this was the case at the time as well. They simply had a power that was unquestionable, deriving from the perfection of their form, quite unlike anything found in the natural world.

Their rounded shapes makes me think of another far rarer class of grave goods, the strange burial drums found in England, chalk objects inscribed with abstract markings that were probably made around the same time as the Liangzhu Bi disc above.

Only around five are known, but many more must still lie buried. Here is one of the ‘Folkton drums’, found in the grave of a child in Yorkshire.

Two, imageless images

Both Buddhism and Christianity began as ‘aniconic’ religions, which is to say that there were at first no images of Siddartha Gautama or of Jesus Christ.

In both cases the ‘heroes’ of the faith were represented for hundreds of years by symbols.

The Buddha was represented by his footprints or by an empty throne, Christ by the image of a fish, or by the Chi-Rho symbol, an overlaid ‘X’ and ‘P’, the first two letters of his name in Greek.

Was it the first logo?

In the case of Buddhism, images must have seemed unnecessary for a religion based on closed-eye meditation, and for which there was no creator God. Christianity was a secretive cult, and so evolved a symbolic world out of necessity. In both cases there was a necessary ambiguity, an open-ended symbol that did not attempt to fix down the likeness or the character of the central character in the story.

Three, how do you know what they looked like?

In the third century AD images of Christ, and also of the Buddha began appearing. Nobody quite knows why this happened. Perhaps it was simply the result of curiosity, or the changing profile of both religions, spreading over wide areas, being considered not as localised cults, but rather as social movements, in need of personalisation and advertisement.

For those tasked with making images of both leaders, the problem was acute. Neither in early Buddhist texts (as far as I know), or in the Bible, are there any visual descriptions that might have helped. Did Jesus have a beard? How tall was he? Any distinguishing features? The Bible is a remarkably unvisual book.

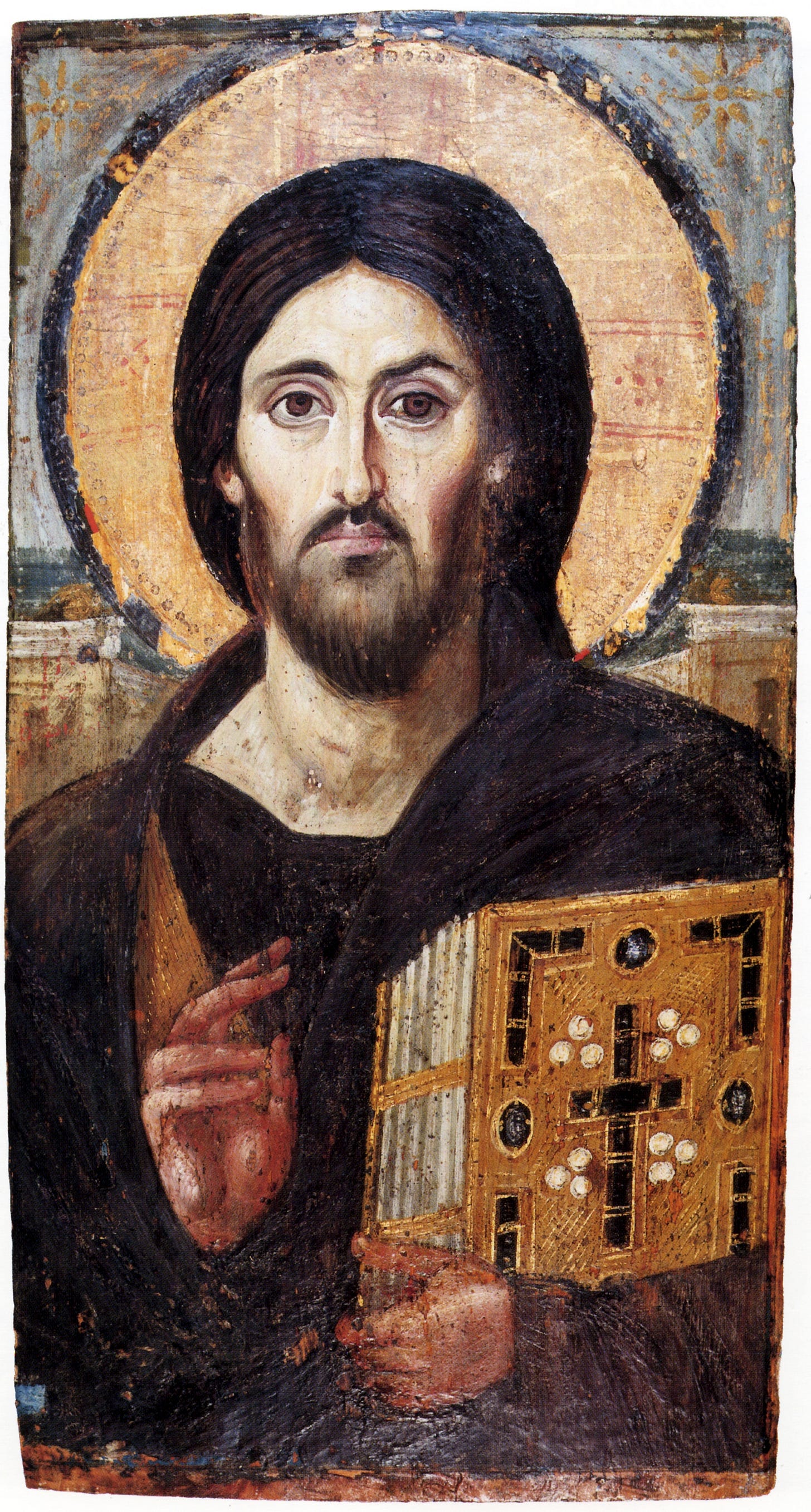

Sculptors and painters looked to the past for their models, at first showing Christ as a Roman emperor - he was after all the ruler of a spiritual empire. It was only a few centuries later that Christ began looking like Christ - bearded, serious, wise beyond his thirty-something years.

The ‘Pantokrator’ icon, preserved at Saint Catherine’s monastery in Sinai, is famous for showing his face asymmetrically, as if to signal the ambiguity of his dual nature as human and divine.

The image of the Buddha is generally more static, and endlessly repeated — although the similarities with images of Christ are not hard to discern. Christ’s gesture of blessing in the Pantocrator from Sinai appears very much like the abahyamudra of the Buddha — the beautiful hand signal, ‘have no fear’.

For me, the images of the Bodhisattvas, the divine beings who eschew eternity to return and help us mere mortals, are among the most moving Buddhist sculptures.

Here is the Bhodissatva Guanyin, who I always stop to talk to when visiting the museum where they reside, ever since spending a week drawing him while a student.

The name ‘Bhodissatva’, means (I have just learned this) ‘the one who always hear sounds’. It has a wonderful, living, listening quality, and a great aura of ambiguity — is this a prince or a traveller, a man or a woman, a divine being or mortal?

Four, magic powers and living things

With the Christ Pantocrator, as with the many statues of the Buddha and the Bhoddisatvas, we seem to be moving into a different realm — the less ambiguous space of figurative art.

And yet the magic remains — it is the power of not quite knowing how something is done, where it comes from. We are looking at something, and cannot doubt its existence, but still cannot quite believe our eyes.

I mentioned earlier the essay by Alfred Gell, ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’ — an essay that should be read by anyone interested in art and AI.

Gell's argument is that works of art have an effect on us through the technical virtuosity with which they are made — it is the magic of their making that impresses us - that we do not know quite how it was done.

It is an essay I love for its insouciance and occasional silliness — Gell describes at some length how impressed he was as a boy by a matchstick model of Salisbury cathedral.

But it remains a good illustration of his point that it is the mystery of the creative act that gives art its power, and that this is not simply about virtuosic lifelike painting, but about some broader idea of creative inspiration. He talks of:

'...the essential alchemy of art, which is to make what is not out of what is, and to make what is out of what is not'.

The best example of this ambiguity would be Ice Age art — the caves at Chauvet, Niaux, or Altamira, with images of animals drawn and incised on their walls — they still seem scarcely believable for their expressive power, and for the physical effort that must have been expended in their making.

There is a sense of magic that has always gathered around images of animals and, although in the western world they disappeared from human consciousness for over a thousand years (John Berger wrote the best essay on this yet published ‘Why Look at Animals’), their forms remained part of the repertoire of one of the longest traditions of art, the ‘Animal Style’ that dominated the Eurasian Steppes and the imaginations of the Anglo-Saxons as much as those who settled on the Northwest Pacific Coast of America.

Five, words as images

All religion based on scripture has at some point transformed words into images, as a way of pointing to the revelations of hidden wisdom.

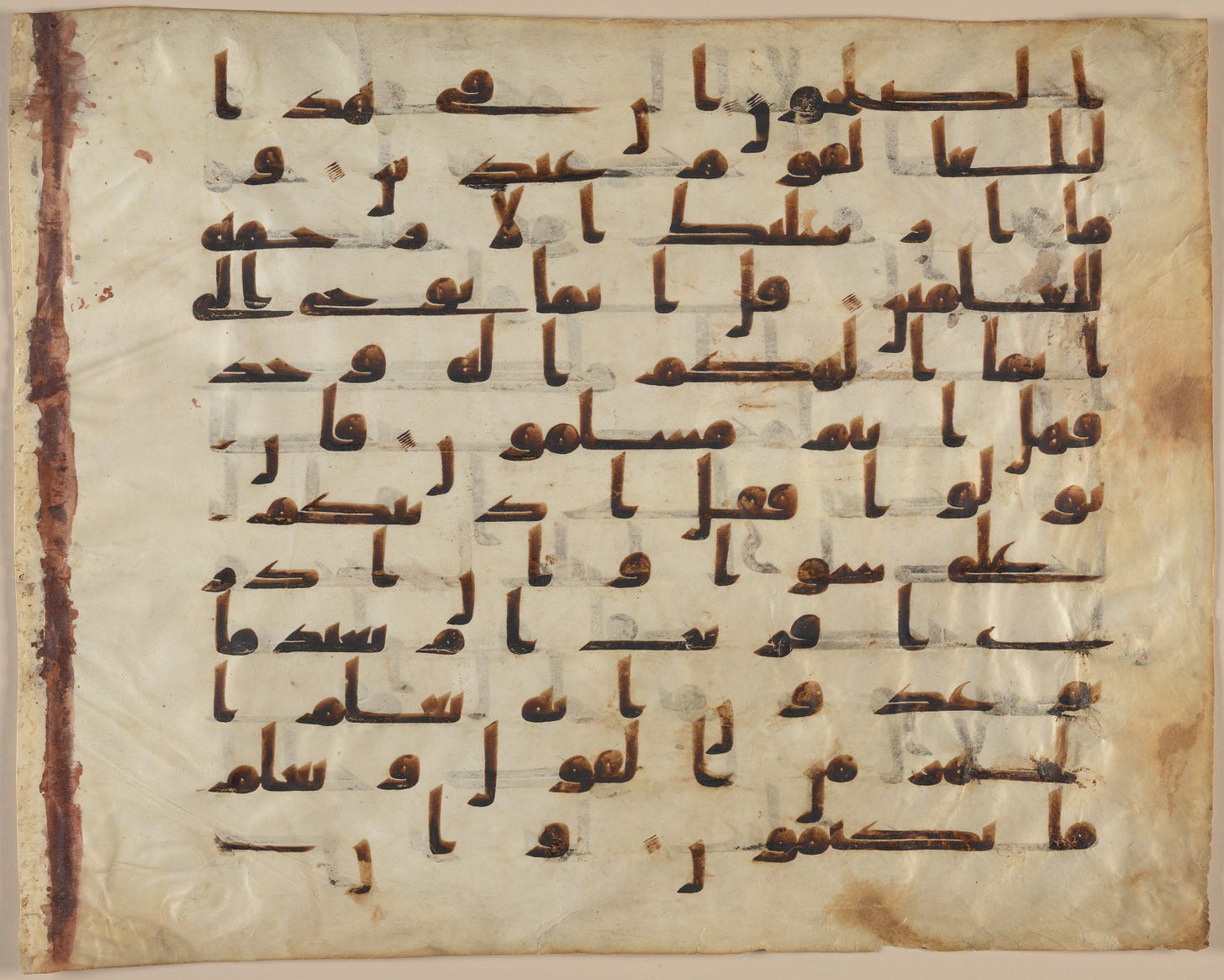

I think of the kufic calligraphy of some of the earliest known Qu’rans (the Tashkent Qu’ran is the best example), in which the words become vital images of the power of faith.

Continuous lines, drawing with unerring perfection of brush, seem the direct imprint of the voice of the imam reading the verses, the muslim scribe’s hand like the stylus of an acoustic sound recording.

Words as images bring their own discourse of ambiguity. That words carry a sacred power is stated directly in the opening of the Gospel of St John — ‘In Principio Erat Verbum’, in the beginning was the word.

Well, yes, said Bishop Eadfrith, creating the Incipit, or opening page of St John in his Lindisfarne Gospel — but in the beginning there was also the world of nature, teeming around the letters with an energy and vitalism that recalls the flowing lines of the Tashkent Qu’ran.

The plenitude of the Lindisfarne Gospels reflects the wider world of Anglo-Saxon manuscript illumination and metalwork, driven by a spirit that abhorred a vacuum — ‘horror vacui’.

It is here that a really interesting divergence becomes apparent.

On the one hand the Lindisfarne Gospels, a combination of the wandering spirit of Celtic art, and the world-filling impulse of the classical world. Nature done in Latin, so to speak.

On the other, a will toward emptiness, an urge towards the dissolution of the self, in the absolute truth contained in the concept of nothingness.

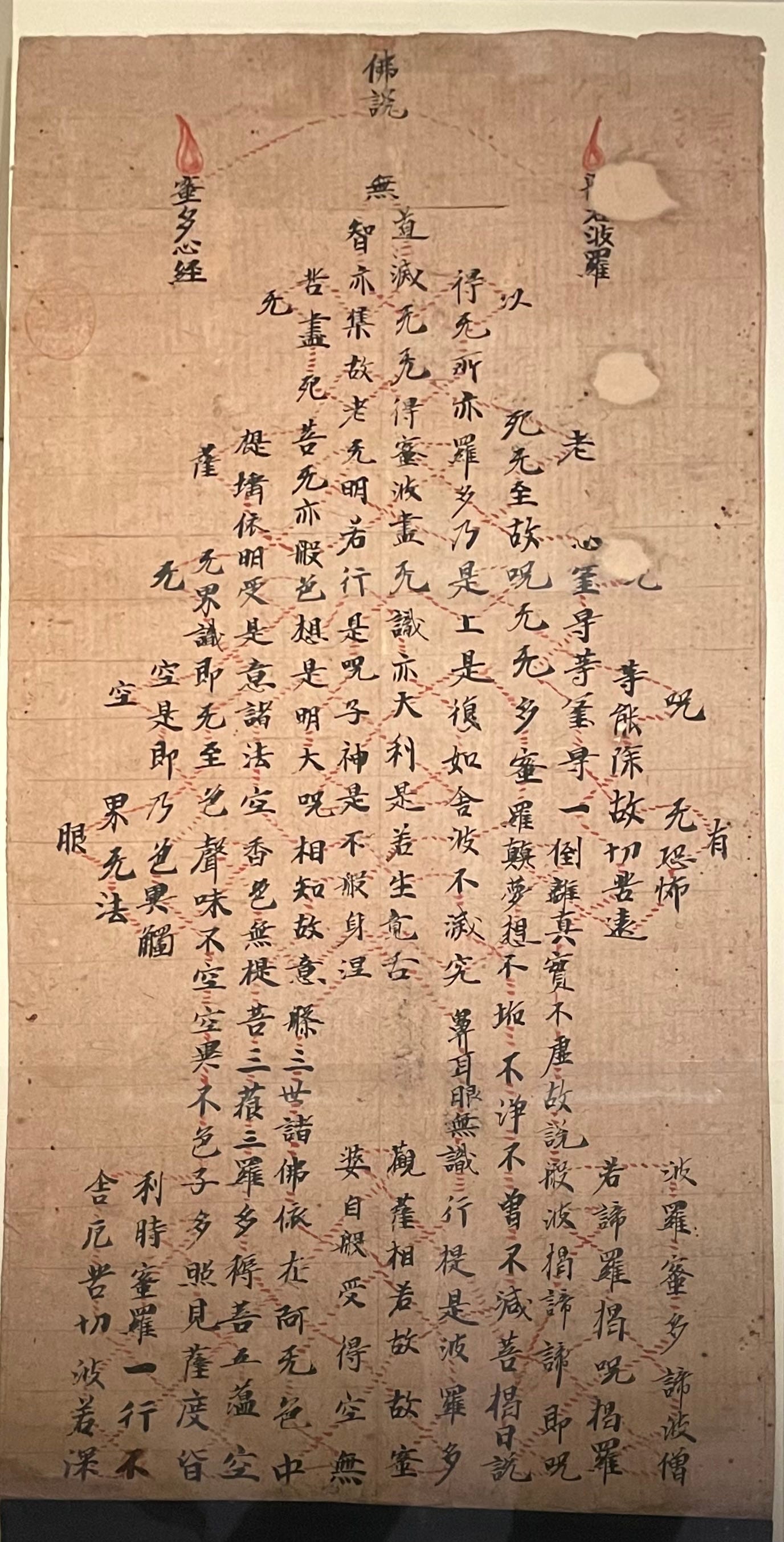

— gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā

— Gone, gone, gone to the distant shore, awakening!

These are the final lines of the Heart Sutra, one of the shortest Buddhist scriptures. In the eighth or ninth century a Chinese scribe created this manuscript copy, the lines of the Sutra intermingled to form the shape of a Stupa, or Buddhist shrine, at the centre of which is a void.

As with the Tashkent Qu’ran and the Lindisfarne Gospels, the ambiguity here is the riddling ambiguity of language and words with their ever-shifting patterns of meaning.

Six, nature as metaphor

The shadowless world of Chinese painting presents another variety of sacred ambiguity. From the tenth century, artists of the Northern Song dynasty began creating images of lofty mountains, rising from the mist, a formula that was repeated by other artists or centuries — they are often, rightly seen as the first true paintings of landscapes for their own sake.

The point was not to be original, but rather to create images that showed a particular sort of communion with nature, often seen as being based on the ambiguities of Daoism, the recognition of some great unifying cosmic force, and the importance of ‘going with the flow’.

Here is one of the most famous paintings from this early landscape tradition, Fan Kuan’s Travellers among Mountains and Streams. Is it a landscape, or the portrait of a mountain? Nature seems given a living voice, much as the icon paintings being produced in Byzantine workshops.

The purpose of such a painting was not to be bought and sold (the literati painters of China were far above that sort of lowly materialism, preferring to exchange their works with one another, or give them away as gifts), but rather as an aid to contemplation, as a means of access to the numinous mysteries of nature.

We might see Fan Kuan’s mountain in ambiguous Romantic terms — a sublime landscape, more or less imbued with divine spirit, and thus more or less melancholy, depending on your frame of mind and the state of your soul.

But there is a different sort of ambiguity at work, one that is about the ungraspability of the passing moment, the mystery of the lived present, of human consciousness itself.

Seven, emptiness, nothingness

Tracing these rather ambiguous ambiguities, I began to notice a pattern.

On the one hand, a western tradition of figuration, of plenitude, a will to fill the world with images, particularly of the human form, and to make those images super-present, if shot through with sacred ambiguity.

On the other a sense of withdrawal, of silent meditation, of a dissolution of self.

You might say that this silence, this withdrawal, is the culminating ambiguity, the mystery of mysteries, the ambiguity into which all the other ambiguities are gathered, and for that reason the most powerful legacy of the Era of Images.

The lecture series Everything Worth Saving continues next week at Snape Maltings with ‘Civilisation and its Discontents’ — Tuesday 25th March at 6.30. Tickets here, and on door.

John-Paul Stonard ‘Works of Art are Living things — should we let them die?’, in The Art Newspaper, April 2025.