Cătălina's Revenge

On a voyage to Târgu Jiu

WERE IT NOT FOR THE ARTIST Milița Petrașcu, one of the greatest sculptures of the last century would never have seen the light of day.

And yet when we read about Constantin Brâncuși’s Endless Column, which stands in the remote western Romanian town of Târgu Jiu, rarely do we encounter Petrașcu’s name, nor the name of the young woman whose bravery in part inspired it, Cătălina, or Ecaterina Teodoroiu.

Cătălina Teodoroiu remains a national hero in Romania for her actions in the famous battle that took place in Târgu Jiu in October 1916, a townsfolk uprising against the ninth German army, culminating in a battle fought on the bridge across the river Jiu.

In a later military action Cătălina was captured, but escaped after killing the German guard with a concealed weapon, and returned to fight the same day, despite having been shot in the leg.

Leading a platoon of men in a counterattack against the German army late in 1917, she was killed by machine-gun fire, shouting, it is said, ‘Forward men! Don’t give up!’. She was fighting to avenge the death of her brother in battle.

The events of October 1916, the bravery of Cătălina and the people of Târgu Jiu, have etched themselves onto the national psyche in Romania.

By the 1930s, it was felt that a memorial was needed for such bravery. It was at this moment that the National League of Romanian Women of Gorj (Târgu Jiu is the county town of Gorj) asked Milița Petrașcu to create such a monument to those who had died defending their town some twenty years earlier.

Petrașcu had already memorialised Cătălina herself, creating a large marble sarcophagus that stands at the centre of Târgu Jiu. In a series of relief carvings, Cătălina is shown growing up in her childhood village, then leading the attack on a German gun emplacement Battle of Mărășești, and finally being carried in death and glory by the soldiers she led as the famous ‘girl lieutenant’.

But instead of accepting the commission for a memorial to the war itself, for some reason, which we can only assume was a form of modesty, Petrașcu passed it to the sculptor from whom she had learned so much living in Paris in the years after the First World War, Constantin Brâncuși.

Brâncuși, as a leading light of the Parisian avant-garde, might have seemed a strange choice for a small provincial town in a highly conservative region. His work was indebted to Romanian folk culture, to wood carving of house posts and death poles,1 images based on forms abstracted from nature — but all the same, it was streamlined cosmopolitan art, and Brâncuși himself had not lived in Romania for over thirty years.

His proposal for an abstract column, rising almost thirty metres from the ground, seems nevertheless to have been accepted immediately by the Romanian women of Gorj.

Perhaps Targu Jiu’s remoteness meant that such things could be got away with — it also helped that the commission came from Arethia Tătărescu, the wife of the former prime minister of Romania, so strings were pulled, and Brâncuși set to work.

TO GET TO TARGU JIU you take the train from Bucharest Nord and travel six hours, or so, depending on how late the train is, travelling across the wide and empty Wallachian plain, ancient Dacia.

Clear sky, endless expanses of ploughed fields, scrubland…

The journey west is like going back in time. A man loads branches into a wooden cart tethered to a white horse. A shepherd wrapped in a dark shawl holds a crook and stands among sheep grazing in dust.

You cross a river run dry, and villages in which all life gathers around the train station. The passing through of a train is an event. People come to watch. The station manager in their red hat and vaguely military uniform takes up their habitual position.

Some stations are small and unmanned, some so run-down they are nothing more than ruins, the roof falling in, the interior a mass of scrub and foliage.

A field is punctuated by small oil wells, a wheel-driven pump rising and falling. Thick tree trunks are stacked precipitously in a timber yard.

The journey is long preparation for the moment of arrival, and the revelation of encounter. The great modern masterpiece, a groundbreaking avant-garde work of sculpture… in a field on the edge of a town as far from Paris, as from Bucharest even, as you could imagine, both in distance and in time.

ALL WORKS OF ART contain within themselves, somehow, an idea, or a notion of time. It can be as simple as a matter of slowness or speed — an insistence on oceanic timelessness, or on the present moment, the right here, right now.

The sculptures of Constantin Brâncuși are definitely of the ‘oceanic’ type. He was the opposite of Dada immediacy, an artist who sought the vastness of space and time in the perfectly formed object. Plato wearing a peasant’s smock.

Such thoughts might be passing through your mind as you alight the train at Târgu Jiu. It is late in arriving, so that you have only a couple of hours of light left at this advanced time of year. Why is time always so short nowadays?

You walk briskly down sleepy crumbling streets, crossing the train line where a rusting sign pointlessly warning Atentie La Tren, then up a neat suburban street, and… there it is, as if waiting for you.

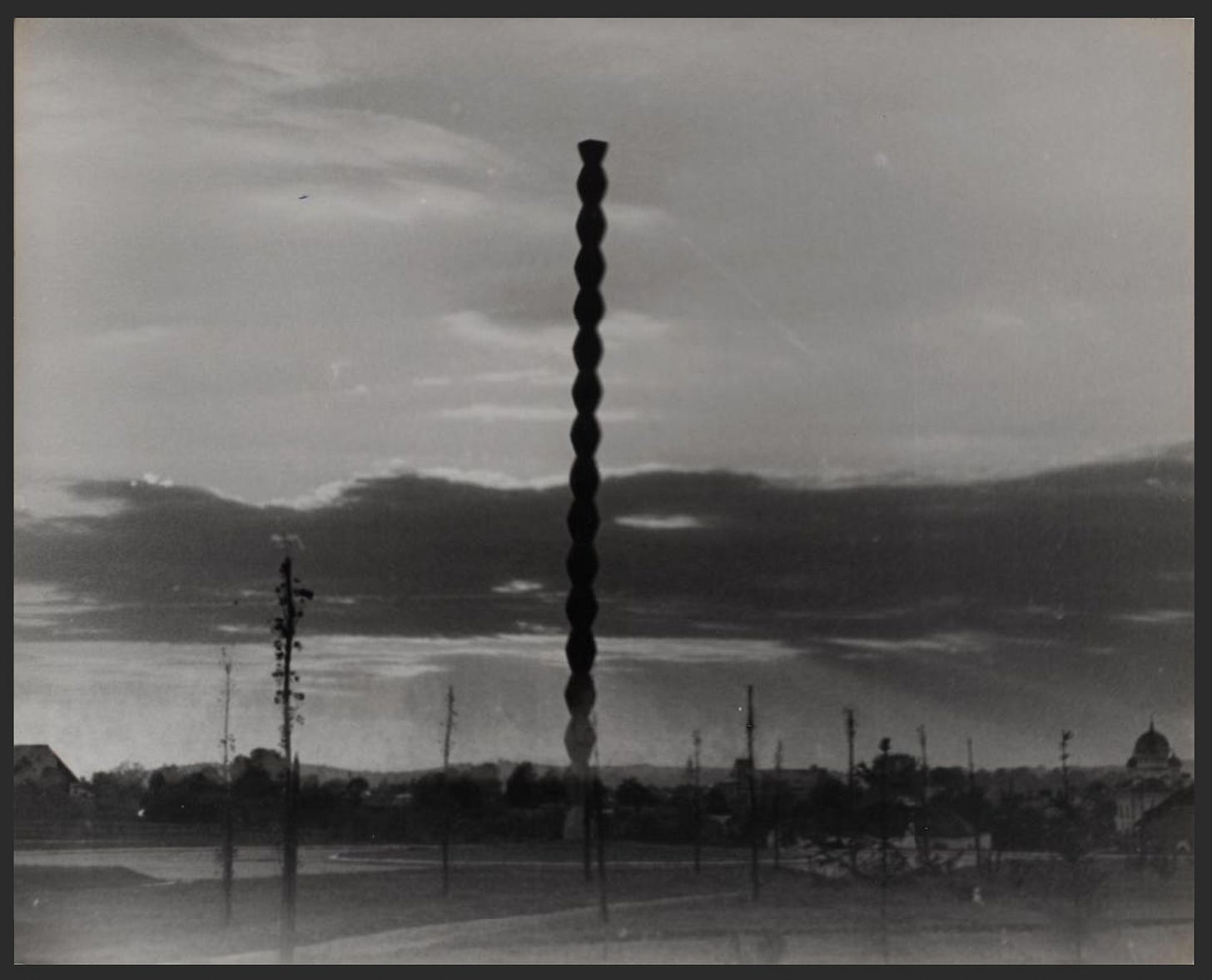

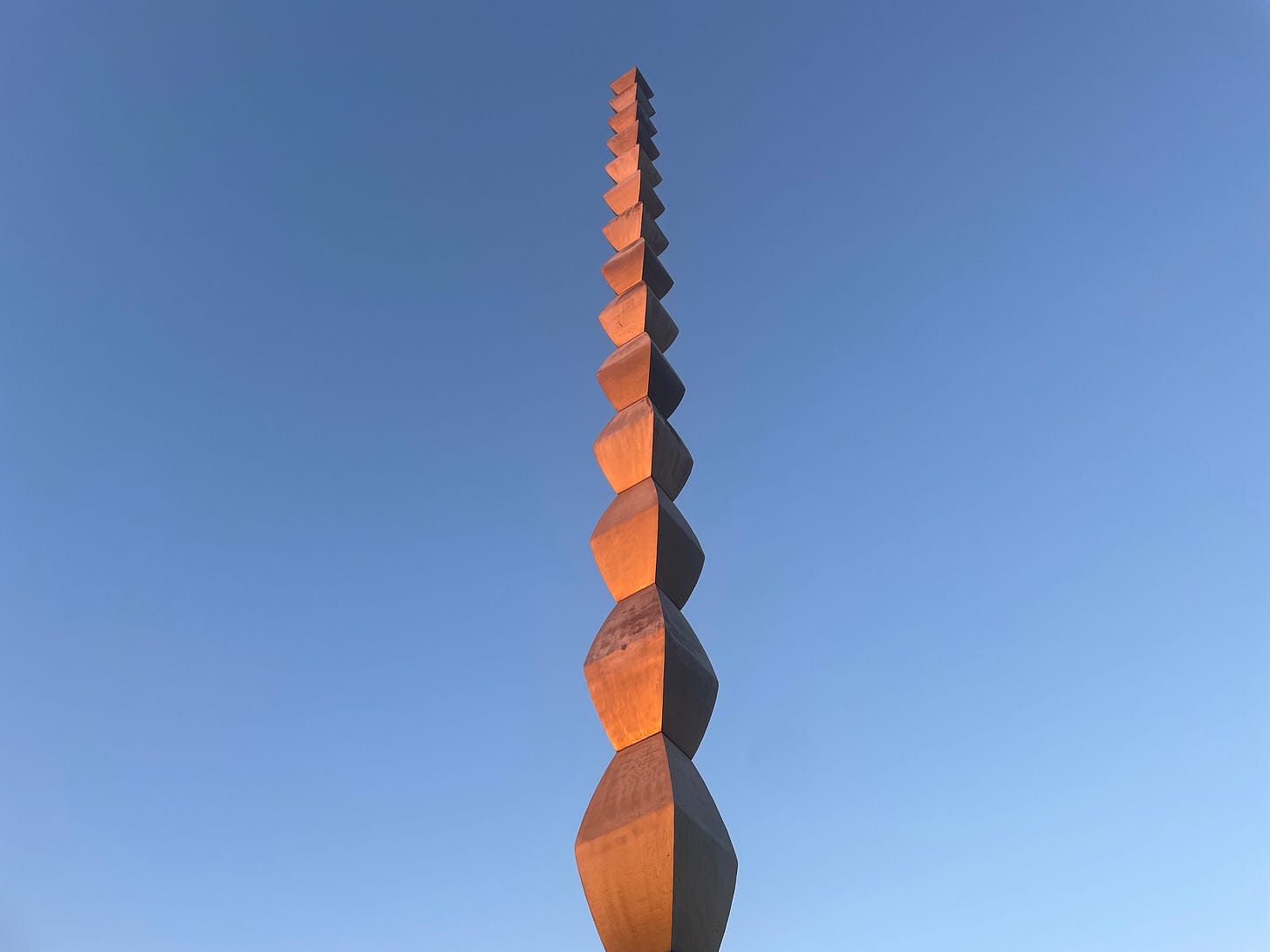

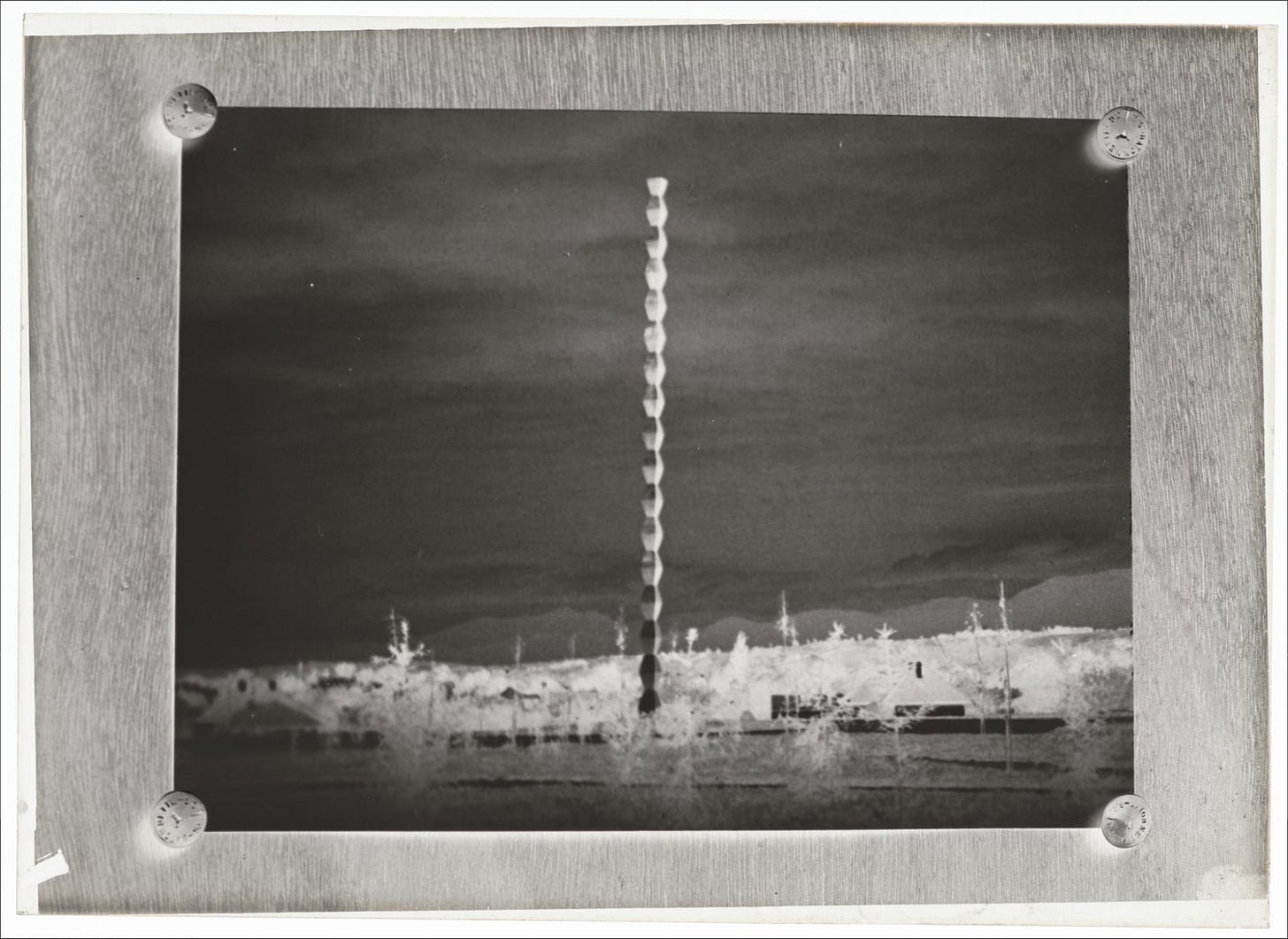

The first impression is of sheer perfection. The regular forms, perfectly straight, rising impossibly into the clear air. The metallic yellow surface glinting like fool’s gold against the clear blue evening sky, mountains spread out in the distance.

You trace your vision upwards and feel the rhythm of the sculpture, the beat of life, ascending. The stacked forms seem weightless threaded together, the whole seeming to rise upward, to exhale and expand. The first and last beads are cut in half, so that it seems without beginning or end — eternity!

The bead-like forms have an innocence, like a giant plaything.

You feel the origins of the Column in the forms of folk art, the simple carved shapes, the repetition, the rhythm.

And then as you tilt back and crane your neck, following the rising forms into the clear blue sky, made even clearer by the wash of evening ozone, you understand the sense of infinity that it brings, a genuine feeling of something that is a piece of something much larger, and yet also complete in itself.

It is cold and the park where the Column stands is empty. A black dog sniffs around the base, then settles at the foot of the column, on a ring of recently-laid gravel.

You try to approach. Perhaps the dog knows something. But a bored-looking official jumps up from a distant bench and calls over, between puffs on a cigarette, that you cannot go up close. Eternity is out of bounds, it seems.

UNESCO flags flutter around. Once the mayor of Târgu Jiu tried to pull the Column down, tethering it to a tractor, or perhaps a horse, in ignorance of the solid steel core onto which the segments are threaded, like beads on a giant child’s toy.

BRANCUSI OFTEN TOLD THE STORY (he told many stories) of being sent out as a boy to herd sheep in the mountains, and making sculptures from the fresh white snow.

There can’t have been many passers-by in this remote region, but those that saw them, Brâncuși would say, sitting around the stove he had made, eating the stew he had cooked, in his studio in the Impasse Ronsin in Paris, would be seriously impressed.

Like the story of the young Giotto, drawing perfect circles in the ground with a stick, whether the story is true is not the point. It is less that Brâncuși was a great sculptor from the outset (which is saying little, as all children are great artists) but more the memory of the whiteness of the snow.

The walls of Brâncuși’s studio in Paris, which doubled as a gallery and showroom of his work, were perfectly white. An art gallery cliché now, in the early years of the twentieth century it was highly unusual.

White became a symbol of something in Brâncuși’s world. It was something uplifting, mind-clearing, inspiring, but also symbolic.

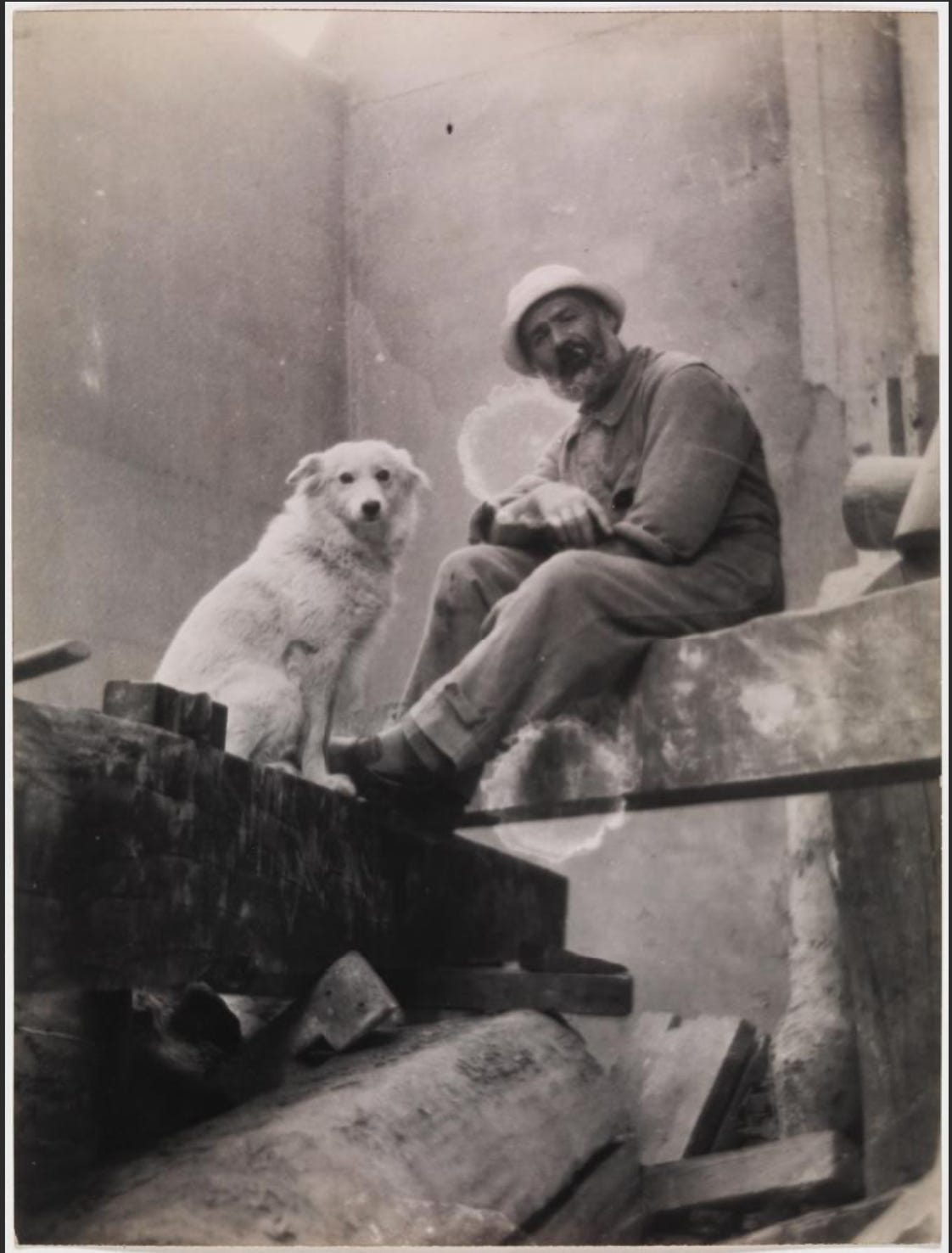

The art historian and artist John Golding, in his great essay on Brâncuși published in Visions of the Modern, wrote that Brâncuși’s dog, Polaire, a perfectly white Siberian herding dog, was a celebrated Parisian beauty, as popular as the artist himself in bohemian circles.

Whiteness, gathered rays of light… all in the service of infinity.

THE FIRST OF THE ENDLESS columns was carved during the First World War, then another, slightly larger, when the war was almost over. Then another still, carved from a tree fallen in the garden of the photographer Edward Steichen at his house in Voulangis, just outside Paris.

Steichen abandoned France, and his house fell into ruin. Brâncuși went along with Man Ray to rescue his column, sawing it in half and loading it on the back of a truck bound for the Impasse Ronsin.

It was like some ‘prehistoric totem pole awaiting ritual’, Man Ray said, a little shaky on the art history. They provided the ritual anyway, setting up a table in Steichen’s dilapidate garden and filming themselves breaking bread and drinking wine.

There were, all told, around six endless columns over the years, carved with sharpened axes and chisels, then cut up again and reassembled.

Sometimes they were mere plinths, sometimes full-blown sculptures. They were always changing. When Marcel Duchamp organised a show of Brâncuși’s sculptures in New York, he sawed a couple of centimetres from the top of two Endless Columns so that they would fit into the gallery.

It is doubtful that Brâncuși would have been too upset — a show in New York was a show in New York, after all.

At Târgu Jiu the Endless Column was not carved but cast, individual rhomboid beads, created in a metal workshop to the north in the Transylvanian mountains, threaded onto a perfectly straight steel shaft, anchored deep in the ground. It was a miracle of engineering, as much as a work of art.

The surface was covered in molten brass, as if coloured by solar rays. A golden totem, as permanent as the sun itself, an undying memory. And yet no sooner had it been installed than it began to degrade, to submit to the ravages of time.

‘WE ARE LIVING the beginning of a new apocalypse’, Brâncuși once said. ‘The deluge is coming. Nothing will be saved. Sculpture will be lost in the sand’.

Perhaps it was merely for effect, or an old man’s grumbling despair. Or perhaps he had realised the truth that Duchamp had been propagating in his work for years, that art was no longer a window onto eternity, that the time of a work of art was the here and now.

All good art comes to an end. Art cannot escape time — unless, perhaps it is an idea. But ideas too can be forgotten. Nothing lasts forever.

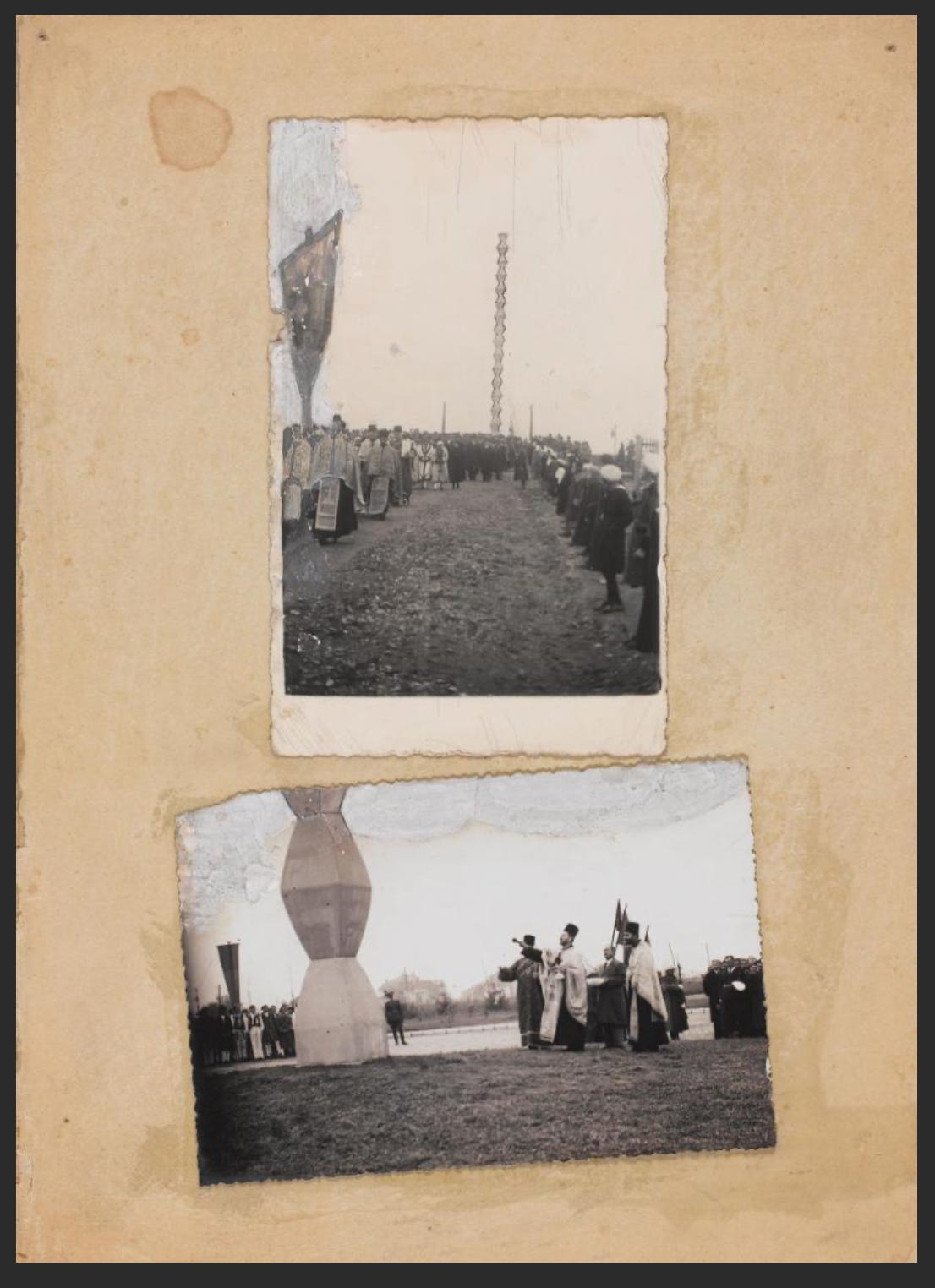

The column was dedicated at the end of October 1938. It is strange to see the Catholic Priests swinging censors and anointing an object that seems so resolutely secular, pagan even — a totem, as Man Ray had put it.

YOU HAVE SEEN photographs in books, but only visiting this small town, cooled by air rolling down off the Carpathian Mountains, do you get a sense of how Brâncuși transformed the entire urban area into a monument to its own survival.

You turn back down the road away from the Column, cross the rusting railway, and then walk a mile down the long straight road known as the Calea Eroilor, the Avenue of Heroes, passing the Romanian Orthodox Church of Saints Peter and Paul (which, despite the traditional forms of its architecture, was consecrated around the same time as the Endless Column).

That late train has given you little time for the rest of the sculptures, but a fine light sky against which to admire their silhouettes.

At the end of the Calea Eroilor you cross a road into a park, and walk under blocky forms of the ‘Gate of the Kiss’, the second part of Brâncuși’s town-wide monument. It is ‘both a genuine gate and the image of a gate’, wrote the sculptor William Tucker.

It is wonderfully naïve and sentimental. The ‘Gate of the Kiss’ is carved with emblems of lovers embracing, echoed by the couples who stand beneath and guilelessly kiss, photographing themselves, making an image of an image.

Further down a path through a wooded area of parkland, passing rows of stone seats, like sections from a toppled Endless Column, pedestals for the broken-hearted, perhaps, until you reach the final sculpture at the end, the mysterious Table of Silence.

Two large cylinders carved from a local stone, bampotoc, form a table surrounded by twelve stone stools. Some have imagined the table as the base of a column stretching into eternity. Others have seen the twelve stone stools as the signs of the zodiac.

‘Do not look for obscure formulations or mysteries’, Brâncuși once said about his sculptures. ‘Look at them until you see them’.

We look and look, but what do we really see? Perhaps it is a matter of what we are not seeing, what has been forgotten in this great striving for eternity? The old lie, as Wilfred Own wrote, of death, glory, eternity, Dulce et Decorum est.

Standing by the side of the River Jiu, gazing at the Table of Silence and back up the long pathway to the Column itself, there seems little to connect Brâncuși’s works to historical events. This was where Cătălina fought off the Germans to avenge the death of her brother. What would she have thought of the Table of Silence, the Gate of the Kiss, the Endless Column? Perhaps nothing, only: ‘Forward men! Don’t give up!’

We seem to have left this story of heroism far behind. What we are encountering is not Cătălina but Constantin. And not a memorial to war, but a memorial to something far more nebulous, ungrounded in historic reality.

You cast your mind back to the Column, which by this late hour must be nothing more than a silhouette against twilight. A memorial to the belief in works of art as a fragment of eternity.

The so-called ‘death poles’ used as grave markers around Oltenia: thin poles, often carved with regular forms, many having a little bird carved at the top. They are said to come from Hungary, where they are known as kopjafa, memories of the warrior’s lance that marked a grave.

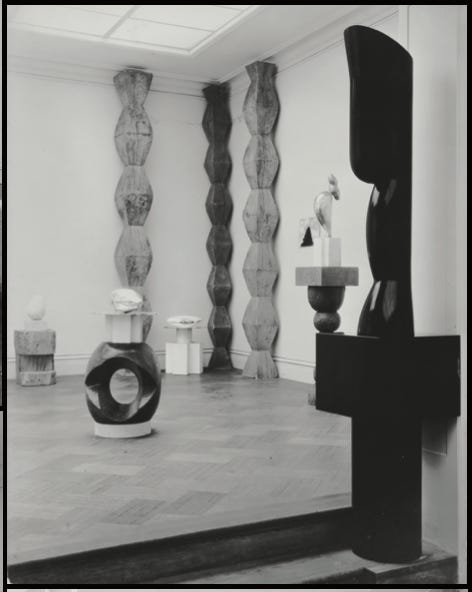

Thank you for a wonderful article, John-Paul. That this extraordinary sculpture, commissioned by a Women's League and built to honor a remarkable woman soldier and the soldiers she led, exists in such a place is itself amazing, and to see "Endless Column" must be thrilling. I am grateful you included the photo from the Pompidou, which gives something of a sense of each module's mass, which leads me to admire all the more the feat of the sculpture's construction and the height achieved. (The website of the World Monuments Fund includes some up-close photographs of the column's spine and how the modules looked after a restoration-and-conservation project. There are also photos of the details to be seen in the Gate.)

This is a wonderful piece John-Paul. Just amazing. The photographs are terrific! Did you by any chance see Adrian Dannatt's exhibition on the Impasse Ronsin in Basle? There is a brilliant book which accompanies it. Brancusi was the only person on the Impasse with hot running water and electricity. Apparently Tinguely, St Phalle et al would pop in for a hot bath and to have a glass of he only thing he kept in his fridge, namely champagne. Class act.