THERE IS A WONDERFUL STORY told by Hans Richter of a performance given by Kurt Schwitters of his famous sound poem, the Ursonate (‘Primal Sonata’).

It was the first public reading of the poem, which Schwitters spent much of the 1920s writing, and took place in a private house in Potsdam. The audience were, Richter writes, the ‘better sort’ of people — retired generals and ‘dignified old ladies’. The Prussian upper echelons, then.1

The Ursonate, if you know it, is not the sort of poem that might ordinarily be read in such a setting. It begins:

Fümms bö wö tää zää Uu, pögiff, kwiee…

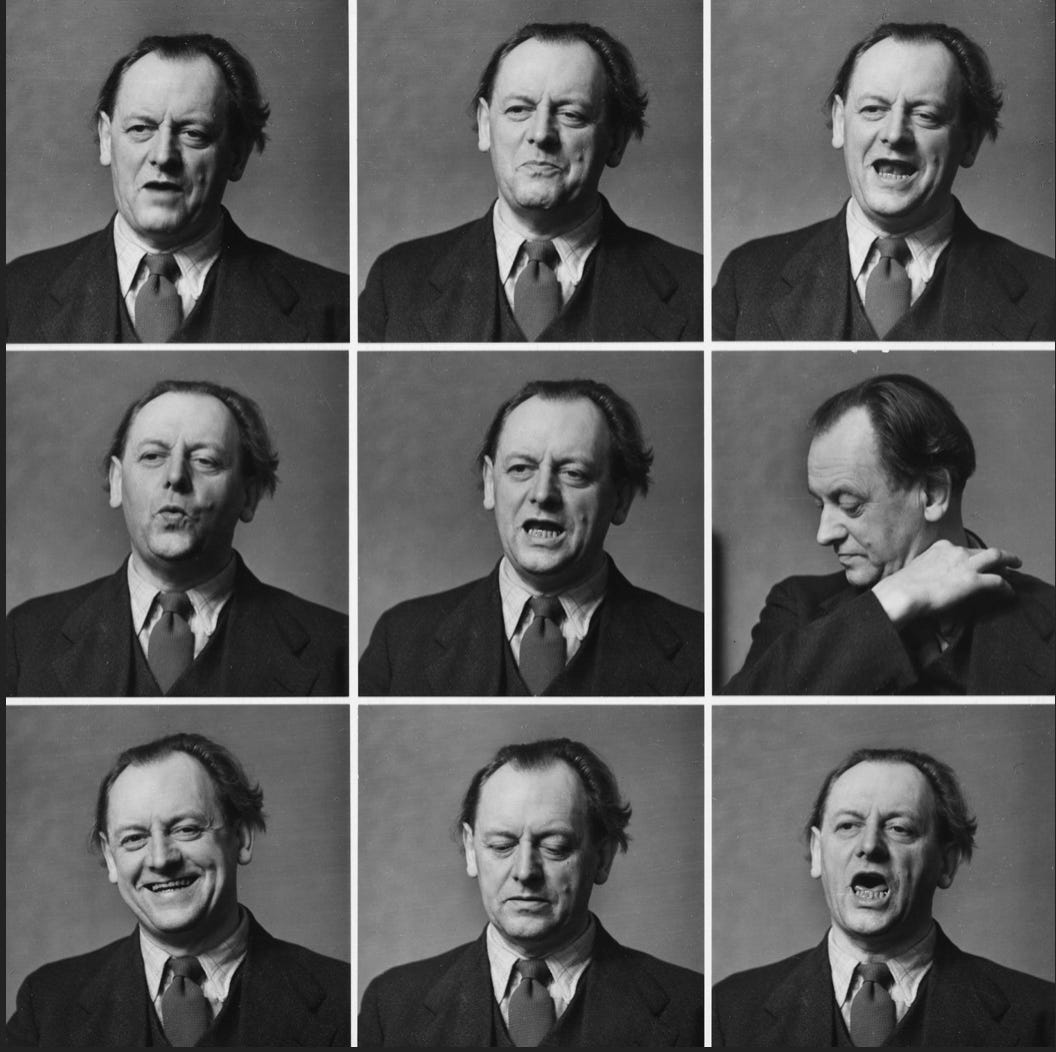

And continues for some forty minutes in a similar vein. It means absolutely nothing, but if recited with conviction, and especially if accompanied by ‘hisses, roars and crowings’, as Schwitters did, ‘before an audience who had no experience whatever of anything modern’, is sure to have some sort of effect.

The audience in Potsdam reacted at first with polite bemusement mingled with shock, but before long the entire room, Richter wrote, erupted in laughter. Schwitters would not be put out, so simply upped the volume of his ‘enormous voice’, so that for a while the room was filled with a mighty din of audience and poet, before the former was vanquished, and Schwitters was able to complete his poem with no more protest or interruption.

The denouement of Richter’s story is the memorable part. When the performance was over, the generals and ladies came to Schwitters ‘with tears in their eyes’, full of admiration and gratitude. ‘Something had been opened up within them, something they had never expected to feel: a great joy’.

This ‘great joy’ is something we all might experience when encountering some new form of expression, some fresh language that awakens us to the world once again. For the Dadaists, such awakening was a consciousness-changing exercise, and the very point of their activities as Dadaists.

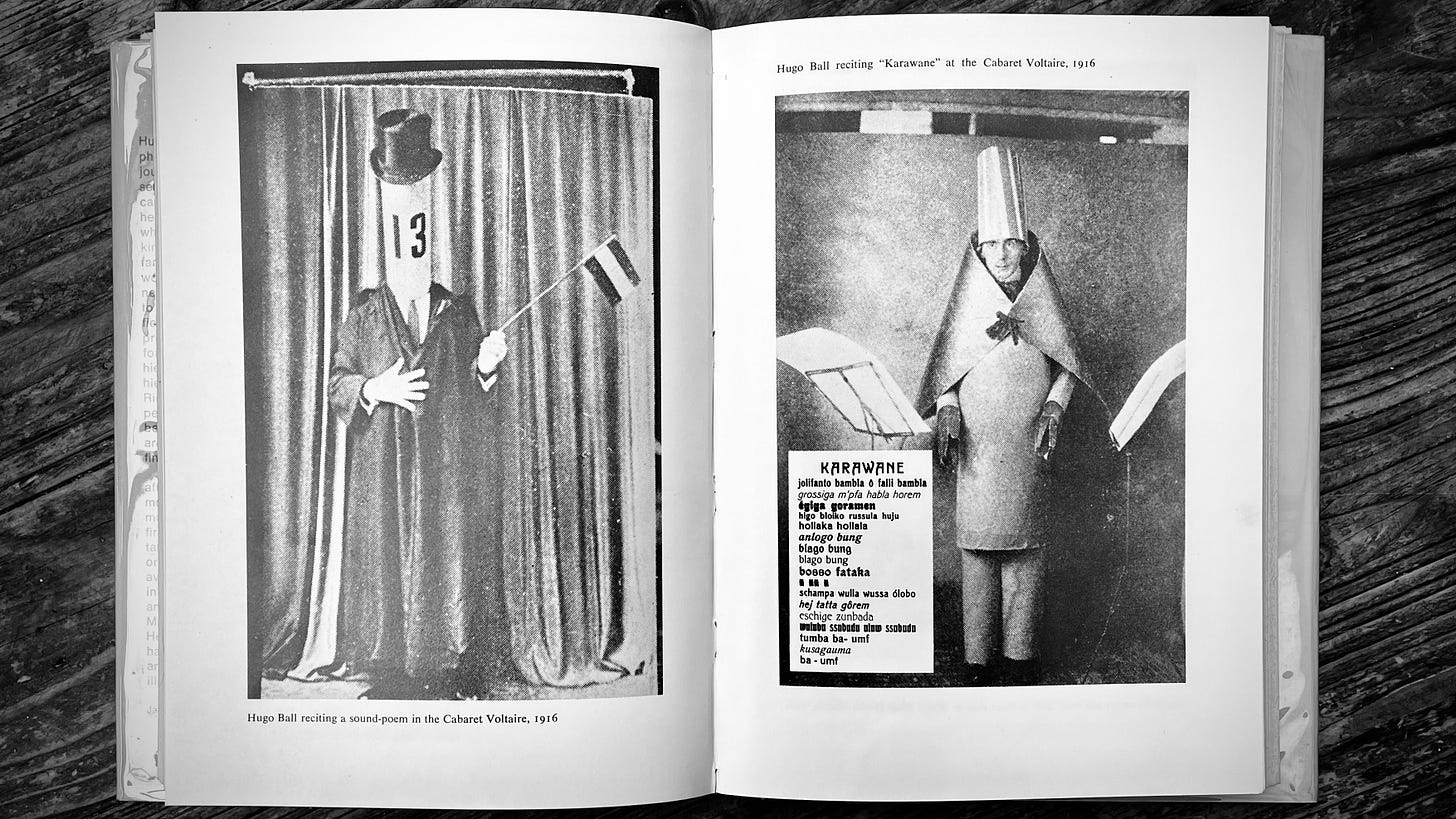

The German writer, and founder of the Dada movement, Hugo Ball, has much to say about phonetic poetry and the power of words in Flight out of Time, his diary describing the origins of Dada in Zurich during the First World War:

The use of ‘grammalogues’, of magical floating words and resonant sounds characterizes the way we […] write. Such word images, when they are successful, are irresistibly and hypnotically engraved on the memory, and the emerge again from the memory with just as little resistance and friction.2

Phonetic poems such as Hugo Ball’s own Karawane were a means, Ball wrote, of liberating words from the conventions of the ‘rational, logically constructed sentence’, as a way of rediscovering the ‘evangelical concept of the “word” (logos) as a magical image complex’.

It was a way of rescuing language from dead metaphor, returning words their enchantment as symbols — but also, as Schwitters well knew, a way of provoking audiences, and of getting a reaction that counted. Phonetic poetry is nothing if not performed, and Dada was — is — something that has to happen on a stage, in front of an audience.

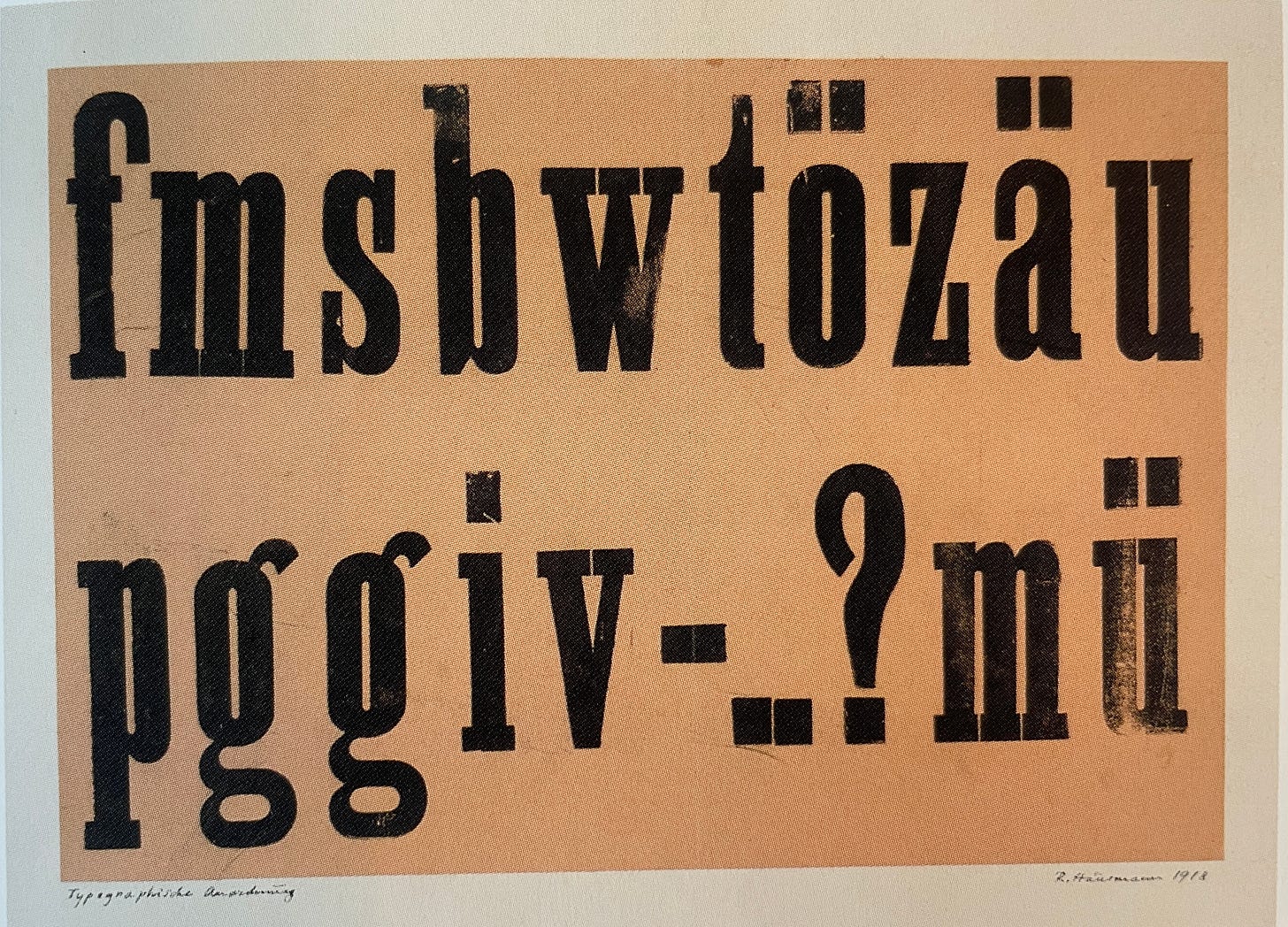

Schwitters derived the first line of his Ursonate (which strictly speaking should be called the Urcantata, as it is spoken-sung, rather than sounded-played), from a poem with the wonderful title fmsbw, by Raoul Hausmann (see image above).

Schwitters had heard Hausmann recited the poem when the two were on a Dada tour in Prague with Hannah Höch in 1921. On a previous visit to Prague, the audience had mounted the stage and physically attacked Hausmann. This was relatively normal for Dada events, a semi-violent carnivalesque atmosphere that can be traced back at least to the first performance of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century.

In fact, on the evening in question, which the trio titled an ‘Anti-Dada-Merz’ tour, Hausmann had begun the Dada soirée by reading a manifesto with the title ‘Présentismus’, about Dada as a means of living in the present moment, and which also contained Hausmann’s description of an Optophone, which could convert audio to visual signals and vice versa — ‘Thanks to electricity we are capable of transforming our haptic emanations into moving colours, into sounds, into new music’.

The audience, who were spoiling for another evening of chaos and violence, clearly found all this so boring that few of them returned after the interval. Or perhaps it was the poems that Schwitters performed that evening, including the self-explanatory ‘Alphabet read Backwards’.

Schwitters made his art through finding things — on the street, in magazines, in his pockets, but also in the minds of other artists. There is no record of what Hausmann thought of Schwitters ‘borrowing’ his ‘fmsbw’ (in fact, his own poem had been created, it seems, through asking a printer to choose random letters from his tray to make four Plakatgedichte, or Poster-poems, a few years earlier), but he is sure to have approved of the reaction of the audience in Potsdam (although other Berlin Dadaists thought that Schwitters consorted too much with the enemy, the po-faced bourgeoisie).

Nobody is shocked by the Ursonate nowadays, but its power of mind-liberation remains. Recordings of Schwitters reading might remind us of the few short recordings of James Joyce reading from Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The music of the language, in Joyce’s singsong Irish, just as much as Schwitters’s distinctive Hannoverian German, makes sense of an otherwise incomprehensible text.

This is the enduring power of phonetic poems, written almost one hundred years ago, but still models of protest and consciousness awakening today.

Hans Richter, Dada art and anti-art, London 1965, pp.142-3

Hugo Ball, Flight out of Time, New York, 1974, p.67